Research Article - (2022) Volume 11, Issue 2

This study was initiated to assess whether dietary diversity and household food insecurity are associated with nutritional status of children western Oromia, Ethiopia. A community based cross sectional study was employed in September, 2020. Multi stages sampling methods were employed. Dietary diversity score, Food Insecurity and anthropometric data were also used. Data was analysed using SPSS version 20.0. Logistic regression analyses were also carried out. The finding of this study showed that poor wealth index and food insecurity were determinants of underweight. Moreover, child birth order above three years, no antenatal care visit, no consumption of wild edible foods and low dietary diversity were determinants of stunting. Furthermore, this study indicated that having a history of sickness, no antenatal care visit and low dietary diversity were determinants of wasting. This study concluded that the prevalence of under-nutrition among young children in the study area is high. Therefore, a community based nutrition education should be done to overcome the problems of under nutrition of children in the study area.

Nutritional status • Dietary diversity • Food security • Children

Adequate nutrition is essential during childhood to ensure healthy growth, proper organ development and function, a strong immune system, and cognitive development. However, the burden of under-nutrition and food insecurity remains a global challenge in sub-Saharan Africa. Despite the overall progress to reduce global food insecurity and chronic undernourishment, sub-Sahara Africa remains the most food-insecure region in the world with close to 223 million people undernourished. This challenge could affect young children, pregnant and lactating women who are the most vulnerable and at high risk. In Ethiopia, magnitude of under-nutrition, low dietary diversity and food insecurity is very high in rural communities where livelihood depends on farming system [1]. The nutritional consequences of food insecurity include under nutrition depending on a broad range of contextual, economic and socio cultural factors. A study conducted in Tigray, Ethiopia, showed that the prevalence of stunting, underweight and wasting in food insecure households was high and 52.1%, 20.5% and 12.6%, respectively. In addition, a study done in south Ethiopia, reported that the prevalence of stunting, underweight and wasting among children was 45.6%, 26.3%, and 14.6%, respectively. Besides, a study done in Ethiopia revealed that the prevalence of stunting, underweight, and wasting was 50.7%, 27.5%, and 5.9%, respectively. A study done by also reported that the prevalence of stunting, underweight and wasting was 42%, 33% and 15%, respectively.

Several factors which are associated with under-nutrition have also been identified; low wealth index. Another factors associated to under-nutrition were food insecurity, no antenatal care visit and birth order. In addition, factor which associated with under nutrition among children was child dietary diversity score. Besides this, diarrhea (sickness) was also another factor associated with under-nutrition. Food is a primary need basic to all human needs and a fundamental human right. Improved food security is vital in the alleviation of poverty, promotion of people’s health and labor productivity, contributes to the political stability of a country and ensures sustainable development of citizens. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) defines food security as a “situation when all people at all times have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs for an active and healthy life”. However, food insecurity remains a major concern for numerous rural households in Sub-Saharan Africa and it influences children nutritional statuses by limiting the quantity and quality of dietary intake. Approximately, one billion people globally are chronically hungry; two billion regularly experience periods of food insecurity. This burden of under- nutrition falls disproportionately on infants and young children and women, especially pregnant and lactating, in low and middleincome countries [2].

According to a study done in South Ethiopia, the prevalence of household food insecurity was high (75.8%) and it was significantly associated with underweight and stunting among children under five years old. Another study done in the three regions of Africa by, also revealed that being stunted or underweight were significantly higher for children in severely food-insecure households in Bangladesh and Ethiopia and in moderately food-insecure households in Vietnam. Moreover, a study done in west Oromia (Ethiopia), indicated that the prevalence of food insecurity was 74.1% and it had association with children underweight.

Dietary diversity is considered to be a key indicator in assessing the access, utilization, and quality of diet of individuals or households. Since no single food can contain all nutrients, the more food groups included in the daily diet, the greater the likelihood of meeting nutrient requirements. Thus, a diet that is sufficiently diverse may reflect nutrient adequacy. The diversity of species used in agricultural and livelihood systems is also essential for human nutrition and sustainable food systems.

Poor dietary diversity is a severe problem among poor communities, especially among children, pregnant and lactating mothers because they require additional energy and nutritious foods for their physiological and mental development. Because low-quality diets are the leading risk factor for ill health worldwide and determined by socioeconomic and other factors including income, education, gender empowerment, and inequality. Studies done in Ethiopia revealed that almost above half percentages of children less than five years had poor dietary diversity score, in Tanzania and in Burkina Faso. Another study done in southwest Ethiopia also shows that only 38% of children met the minimum dietary diversity score [3].

Oromia region is among the regions producing adequate food products in the Ethiopia. Nevertheless, it is reported that there is high prevalence rate of child under nutrition as compared to prevalence rates in less productive regions of Ethiopia. The Ethiopian mini demographic and health survey reported that the prevalence of children stunted, underweight and wasted was 37.5%, 22.2% and 6.9%, respectively in Oromia region. In rural communities, this prevalence of stunting among children in food insecure households was very high (61.1%) compared to those children who lived in food secure households. However, in the study area, there was no study done to assess dietary diversity, household food security and nutritional status of children. Therefore, this study was designed to assess dietary diversity, household food security status and nutritional status of children (aged 24-59 months) in Jima Geneti district, western Oromia, Ethiopia.

Study area

The study was carried out in Jima Geneti district, Horo Guduru Wollega zone, Oromia region, Ethiopia. Jima Geneti is one part of the Horo Gudru Wollega Zone woredas and is bordered on the east by Guduru, on the north by Horo, on the west by east Wollega Zone, on south by Wollega Zone and on the southeast by Jimma Rare. The 2007 national census reported a total population for this woreda of 64,158, of whom 31,756 were men and 32,402 were women; 6,966(10.86%) of its population were urban dwellers.

Study design and period

A community based cross sectional study design was conducted between September to October, 2020.

Source and study population

All children aged 24-59 months in rural communities of Jima Geneti district, Horo Guduru wollega zone were the source population. All children aged 24-59 months in rural communities who were randomly selected from Jima Geneti kebeles were constituted the study population.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Households which are the residents of the study area at least for 6 months and which have children 24-59 months were included in the study area but those farmers/mothers who are chronically sick and not found at home during the time of study were excluded from the study [4].

Sample size determination

The sample size of the study is calculated using formula for a single population proportion by considering the following assumptions; critical value for normal distribution at 95%CI which equals to 1.96 (z value at α=0.05) P=expected prevalence of stunting in Oromia region (27%). d=margin of error 5%). The formula is yielded n=303. Therefore, the total sample size required for this study is 500 children by considering 10% of non-response rate and Design Effect (DE) of 1.5.

Sampling procedures

Jima Geneti district is purposively selected as study site since there was no study done before in the study area regarding assessment of dietary diversity, household food security and nutritional status of children. Therefore, multistages sampling methods will be used to draw samples for the study. From the total fourteen (14) kebeles found in the Jima Geneti district, five kebeles (Gudetu Jima, Hunde Gudina, Gudetu Geneti, Lalisa Biya and Kelela Didimtu) were selected using simple random sampling technique. The children in each kebele were also selected using population proportion to size based on the available data at Horo Guduru Wollega zonal health office. Finally, from each kebele, the eligible children required for the study were selected randomly.

Data collection procedures for survey

The data about socio-demographic and economic, dietary diversity, household food security status and nutritional status in the study area were collected using a structured questionnaire adapted from different relevant studies. The questionnaire was first developed in English and translated into Afan Oromo (a survey language). Then it was translated back to English by different language experts to check for consistency. After training was given for data collectors consecutively for three days, the data were collected by ten enumerators, two supervisors and researchers. At the end of each day, the completeness of questionnaires was checked by the principal investigator.

Socio-demographic and economic data

The data about socio-demographic (age of child, parents educational and occupational status, marital status) and economic factors (wealth index, ownership of land or cattle) were collected from mothers/caregivers.

Dietary diversity data

The Diet Diversity Score and a 24-hour recall method were conducted with mothers regarding child diet intake. Mothers/caregivers are requested to list all the foods consumed by the family both at home and out of the home in the 24 hours preceding the interview. The seven food groups were used for children aged 6-23 months. Considering four food groups as the minimum acceptable dietary diversity, a child with a DDS of <4, was classified as poor dietary diversity and high if a child DDS was ≥ 4.

Household food (in) security data

Household Food Insecurity (HFI) was measured by using the Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS). The mothers were asked nine questions related to the households experience of food insecurity in the past 12 months preceding the survey. Each item starts with an occurrence question that identifies if the condition has been experienced in the household. An affirmative answer was then followed by a frequency of-occurrence question to determine if the condition happened rarely (once or twice), sometimes (3-10 times), or often (˃10 times) during the reference period. The responses were coded as 0=never, 1=rarely, 2=sometimes, or 3=often. From these questions, two indicators of Household Food Insecurity (HFI) were constructed: Household Food Insecurity Access Prevalence (HFIAP) score, which ranges from 0 to 27. The HFIAP indicators were categorized households into four (4) levels of HFI: Food-secure, mild, moderately, and severely food-insecure. For this study, only two levels of Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (food secure and insecure) were used since the sample size was small.

Anthropometric data

The weight and height of the child were measured using electronic digital weight scale and vertical wooden height board, respectively. The age of the child was calculated in months from their birth date to the day of data collection using a local event.

Variables of the study

In this study, under-nutrition (stunting, underweight and wasting) of children was used as dependent variables while socio-demographic and economic factors, household food security status, child dietary diversity score were used as independent variables.

Data analysis

Data were entered in to SPSS statistical software version 24.0. Before the analysis, data were checked for completeness and then cleaned. Descriptive statistics was run using tables, graphs, and percentage points was calculated to describe household food security status, dietary diversity score and nutritional status of children in the of study area. Height for age, weight for age and weight for height of children were generated from WHO growth standards using WHO Anthro program, version 3.2.2. A child was considered as stunted, underweight and wasted if Z score was <-2 for each index. Both bivariate and multivariate logistic regression was used to identify factors associated to nutritional status of children and p-value less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. The degree of association between dependent and independent variables was reported using Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) and 95% CI.

Socio-demographic and economic characteristics of participants

A total of 500 households were included in this study with a response rate of 100%. Of the total participants, about 472 (94.4%) mothers were married. Four hundred six (81.2%) mothers had no formal education. This study also shows that about 313 (62.6%) participants had family size greater than five. in the study were Protestant and Orthodox religion, respectively. Regarding the wealth status, about 296 (59.2%), 113 (22.6%) and 91(18.2%) households were categorized as low, medium and high wealth index, respectively. The details information of background and economic characteristics of the respondents is listed in the below (Table 1).

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age of the child (in months) | ||

| 6-8 months | 185 | 37 |

| 9-11 months | 212 | 42.4 |

| 12-23 months | 103 | 20.6 |

| Birth order of the child | ||

| First | 86 | 17.2 |

| Second | 99 | 19.8 |

| Third and above | 315 | 63 |

| Maternal age (in years) | ||

| < 25 years | 124 | 24.6 |

| 25-36 years | 218 | 43.6 |

| = 36 years | 158 | 31.6 |

| Religion | ||

| Orthodox | 82 | 16.4 |

| Muslim | 117 | 23.4 |

| Protestant and others | 301 | 60.2 |

| Marital status of the mother | ||

| Single | 8 | 1.6 |

| Married | 472 | 94.4 |

| Divorced and others | 20 | 4 |

| Education status of the mother | ||

| Attend formal education | 94 | 18.8 |

| Not attend formal education | 406 | 81.2 |

| Occupational status of the mother | ||

| House wife | 369 | 73.8 |

| Farmer | 12 | 2.4 |

| Gov’t employment | 24 | 4.8 |

| Merchant | 57 | 11.4 |

| Daily labor | 38 | 7.6 |

| Education status of the mother | ||

| Attend formal education | 123 | 24.6 |

| Not attend formal education | 377 | 75.4 |

| Occupational status of the father | ||

| Farmer | 371 | 74.2 |

| Gov’t employment | 56 | 11.2 |

| Merchant | 29 | 5.8 |

| Daily labor | 44 | 8.8 |

| Household family size | ||

| <5 | 187 | 37.4 |

| = 5 | 313 | 62.6 |

| Household wealth index | ||

| Low | 296 | 59.2 |

| Medium | 113 | 22.6 |

| High | 91 | 18.2 |

Table 1: Socio-demographic and economic characteristics of participants at western Oromia, Ethiopia, 2020.

Child dietary diversity scores

The finding of this study reported that about 469 (93.8%) participants had no home gardens while 151 (30.2%) children consumed wild edible foods during the past 24 hrs before the survey. The below Tables 2 and 3 also shows that almost about 428 (85.5%) and 398 (79.6%) children consumed cereals and legumes based foods, respectively. Moreover, this result reports that about 413 (82.6%) children did not get meat/poultry/fish during the survey in the study area. Concerning the dietary diversity scores of children, about 239 (47.8%) and 261 (52.2%) children had high (≥ 4) and low (≤ 3) dietary diversity scores, respectively.

| Food groups | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Did you have home gardens? | ||

| Yes | 31 | 6.2 |

| No | 469 | 93.8 |

| Cereals/Root/Tubers | ||

| Yes | 428 | 85.5 |

| No | 72 | 14.4 |

| Legumes/Nuts | ||

| Yes | 398 | 79.6 |

| No | 102 | 20.4 |

| Milk, dairy and dairy products | ||

| Yes | 273 | 54.6 |

| No | 227 | 45.4 |

| Meat/fish/poultry | ||

| Yes | 87 | 17.4 |

| No | 413 | 82.6 |

| Eggs | ||

| Yes | 223 | 44.6 |

| No | 277 | 55.4 |

| Other fruits and vegetables | ||

| Yes | 114 | 22.8 |

| No | 386 | 77.2 |

| Vitamin A rich fruits and vegetables | ||

| Yes | 93 | 18.6 |

| No | 407 | 81.4 |

| Wild edible foods | ||

| Yes | 151 | 30.2 |

| No | 349 | 69.8 |

| Dietary diversity scores | ||

| High (= 4) | 239 | 47.8 |

| Low (= 3) | 261 | 52.2 |

Table 2: Dietary diversity Scores of the study children at western Oromia, Ethiopia, 2020.

Household food security status

Based on the responses to the nine generic occurrence questions, about 143 (28.6%) households were unable to eat the kinds of foods he/she preferred during the past thirty days. This study also reports that about 313 (62.6%) and 123 (24.6%) households ate a smaller meal than he/she felt was needed and ate fewer meals in a day, respectively. In addition, the below Tables 3 and 4 also shows that about 106 (21.2%) households went to sleep at night hungry. Regarding, household food security status, about 402 (80.4%) and 98 (19.6%) households were household food secure and insecure, respectively.

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Worried about not having enough food | ||

| Yes | 86 | 17.2 |

| No | 414 | 82.8 |

| Not able to eat the kinds of foods he/she preferred, | ||

| Yes | 143 | 28.6 |

| No | 357 | 71.4 |

| Ate just a few kinds of food day after day | ||

| Yes | 119 | 23.8 |

| No | 381 | 76.2 |

| Ate food that he/she preferred not to eat, | ||

| Yes | 247 | 49.4 |

| No | 253 | 50.6 |

| Ate a smaller meal than he/she felt was needed | ||

| Yes | 313 | 62.6 |

| No | 187 | 37.4 |

| Ate fewer meals in a day | ||

| Yes | 123 | 24.6 |

| No | 377 | 75.4 |

| No food at all | ||

| Yes | 43 | 8.6 |

| No | 457 | 91.4 |

| Went to sleep at night hungry | ||

| Yes | 106 | 21.2 |

| No | 394 | 78.8 |

| Household Food security status | ||

| Food secure | 402 | 80.4 |

| Food insecure | 98 | 19.6 |

Table 3: Irrigation scheduling of wheat for irrigated and heat stress condition.

| Variables | Underweight | COR | AOR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Underweight, N (%) | Normal, N (%) | (95%CI) | (95%CI) | |

| Family size | ||||

| <5 | 124 (51.2) | 160 (62.0) | 1 | 1 |

| = 5 | 118 (48.7) | 98 (37.9) | 2.1 (1.31,3.29) | 2.62 (0.72,3.55) |

| Child sickness in the past two weeks | ||||

| Yes | 76 (22.48) | 121(74.7) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 262 (77.5) | 41(25.3) | 1.27 (1.42,3.41) | 2.9 (0.92,7.2) |

| Wealth index | ||||

| High | 56 (37.1) | 92(26.4) | 1 | 1 |

| Medium | 22 (14.57) | 112 (32.1) | 3.69 (3.3, 9.94) | 4.78 (0.85, 8.83) |

| Low | 73 (48.3) | 145 (41.5) | 2.76 (2.924, 3.11) | 1.4 (2.3, 4.8) |

| Birth order of the child | ||||

| First | 103 (34.0) | 92(46.7) | 1 | 1 |

| Second | 76 (25.08) | 68 (34.52) | 1.52 (0.99,2.32) | 78 (0.92, 4.54) |

| Third and above | 124 (40.9) | 37 (18.78) | 1.36 (1.67,3.31) | 1.83 (0.87, 2.94) |

| ANC visit | ||||

| Yes | 115 (36.4) | 86(46.74) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 201 (63.6) | 98(53.26) | 1.48 (1.08,2.30) | 1.68 (0.78,3.38 |

| Wild edible food consumption | ||||

| Yes | 109 (40.98) | 113 (48.3) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 157 (59.0) | 121 (51.7) | 1.32 (0.90,1.92) | 1.65 (0.98,3.65) |

| Dietary diversity scores | ||||

| Good | 79 (23.87) | 119 (70.4) | 1 | 1 |

| Poor | 252 (76.1) | 50 (29.6) | 1.42 (1.06,1.96) | 1.34 (0.94,2.98) |

| Food security | ||||

| food secure | 122 (42.1) | 62 (29.5) | 1 | 1 |

| Food insecure | 168 (57.9) | 148 (70.5) | 4.06 (2.86,5.78) | 3.2 (2.3,4.82) |

Table 4: Factors associated with underweight among children in western Oromia, Ethiopia, 2020 (n=500).

Nutritional status of children

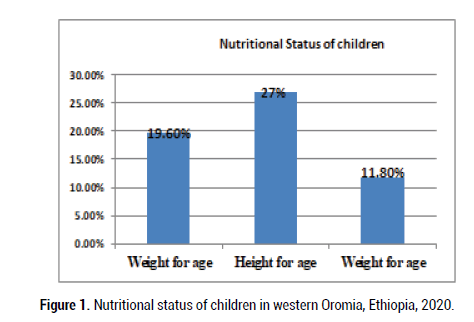

The below Figure 1 shows that the weight for age z-score, height for age z-score and weight for height z-score among children aged 6-23 months was 19.6%, 27% and 11.8%, respectively.

Figure 1: Nutritional status of children in western Oromia, Ethiopia, 2020.

Factors associated to nutritional status

In this study, wealth index and food security status were factors associated with underweight (Table 4). While birth order and wild edible food intake were significantly associated with stunting (Table 5), child sickness was associated with wasting in this study (Table 5). However, both child dietary diversity score and antenatal care visit were associated with stunting and wasting (Table 5).

| Variables | Wasting status | COR | AOR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wasting, N (%) | Normal, N (%) | (95%CI) | (95%CI) | |

| Family size | ||||

| <5 | 84 (36.7) | 164 (60.5) | 1 | 1 |

| = 5 | 145 (63.3) | 107 (39.5) | 2.76 (1.28, 6.79) | 2.32 (0.95, 4.62) |

| Child sickness in the past two weeks | ||||

| Yes | 156 (58.4) | 95 (40.8) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 111 (41.6) | 138 (59.2) | 2.4 (1.58,4.66) | 2.5 (2.82,3.4) |

| Timely started complementary feeding | ||||

| Yes | 153 (61.4) | 119 (47.4) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 96 (38.5) | 132 (52.6) | 3.24(2.35, 6.81) | 2.9(0.91,7.25) |

| Birth order of the child | ||||

| First | 62 (31.0) | 102 (34.0) 300 | 1 | 1 |

| Second | 30 (15.0) | 92 (30.7) | 0.72 (0.41,4.96) | 2.31 (0.94,3.26) |

| Third and above | 108 (54.0) | 106 (35.3) | 2.43 (1.78,3.31)* | 2.21 (0.98,3.88) |

| ANC visit | ||||

| Yes | 215 (69.8) | 70 (36.5) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 93 (30.2) | 122 (63.5) | 4.96 (3.49, 9.56)* | 4.28 (2.13, 8.63)** |

| Wild edible food consumption | ||||

| Yes | 180 (65.2) | 77 (34.4) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 96 (34.8) | 147 (65.6) | 2.69 (1.51, 4.79)* | 1.2 (0.83, 3.82) |

| Dietary diversity scores | ||||

| Good | 82 (57.3) | 114 (32.0) | 1 | 1 |

| Poor | 61 (42.6) | 243 (68.1) | 4.43 (1.42,9.94)* | 3.4 (3.1,7.87)** |

| Food security | ||||

| food secure | 31 (13.4) | 182 (68.0) | 1 | |

| Food insecure | 201 (86.6) | 86 (32.0) | 2.27 (0.93, 5.55) | - |

Note: *Gender, Age; **Gender; AOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio; COR: Crude Odds Ratio

Table 5: Factors associated with wasting among children in western Oromia, Ethiopia, 2020 (n=500).

Child malnutrition continues to be a major public health problem in developing countries including Ethiopia. Therefore, this study provided the opportunity to assess dietary diversity, household food security and nutritional status of children aged 24-59 months in Jima Geneti District, western Oromia, Ethiopia. The current study illustrated that about 19.6% of households in the study area was food insecure. The prevalence of this setting was lower than studies done in the three regions of Africa and Ethiopia. However, this study result was higher compared to a study done in New Zealand. This situation could be due to the variation in sample size of the survey, ecological and economic status of the surveyed communities. Considering Dietary Diversity (DD) score of children, the current study revealed that almost above half (52.2%) of children in this study had low dietary diversity. This finding was lower compared to other studies done in Ethiopia, in Tanzania and in Burkina Faso. However, the current prevalence of this study was higher than studies done in Ethiopia and India. According to the finding of this study, the prevalence of wasting, stunting and underweight was 11.8, 27.1% and 19.6%, respectively. This finding was found to be higher compared to studies done in Vietnam and Ethiopia. However, it was lower than studies done in Bangladesh and Ethiopia. This could be due to the present survey was conducted in the postharvest season which may increase food availability, accessibility and utilization by communities at household level and further lower the prevalence of under-nutrition [5].

In this study, children who lived in households of low wealth index swere 1.4 times more likely to underweight compared to those who lived in high wealth index (AOR=1.4, (95% CI=2.3, 4.8)). The result of this study was in line with studies done in Ethiopia. The finding of the present study was also agreed with other studies done in Ethiopia, in Bangladesh and Sub-Sahara Africa. The finding of the current study also showed that children who lived in household food insecure were 3.2 times more like to underweight than those who lived in food secure (AOR=3.21.4, (95% CI=2.3,4.82). This finding was similar with studies done in in Ethiopia and Nepal. This could be due to the fact that food secure households are able to food access and provide it for their family [6].

Regarding stunting, this study found that children who had birth order three and above were 2.21 times more likely to stunted compared to those children who their birth order was first (AOR=2.21, (95% CI= 1.21,3.58)). This finding was consistent with studies done in Ethiopia and Bangladeshi. In addition, this study implied that those children who had low DD (≤ 3) were 2.4 times more likely to stunted compared to those children who had DD ≥ 4 (AOR= 2.41, (95% CI=1.36, 4.37)). The finding of this study was in line with studies done in in Ghana, Ethiopia, in Tanzania, in Burkina Faso and in Nigeria, The result of this current study also found that children who did not consume wild edible food were 6.8 times more likely to stunted compared to those who did (AOR=6.8, (95% CI=3.81, 14. 12)). This could be due to the fact that wild edible foods are rich in micronutrients and vital for growth and mental development and further it used in preventing malnutrition problem.

In the multivariate analysis of this study, children who had sickness before the survey were 2.5 times more likely to wasted compared with those who had no sickness (AOR=2.5, (95% CI=2.82, 3.4)). The result of this study was in line with studies done in Sub-Sahara Africa, in Ethiopia, in Bangladesh and in Burkina Faso. This could be due to the sickness can lead children to weight loss and further increase the prevalence of wasting. Moreover, this present study revealed that mothers who did not follow up antenatal care had children who were 4.28 times more likely to wasted (AOR=4.28, (95% CI=2.13, 8.63)). The finding was in line with a study done in Ethiopia, which reported that mothers who did not follow antenatal care visit had children who were more likely to wasted compared those mothers who did it. Furthermore, this study implied that children who consumed low DD were 3.4 times more likely to wasted (AOR=3.4, (95% CI=3.1, 7.87)), compared to those who had good dietary diversity ≥ 4 food groups. This finding was similar with the study result done in northern Ghana.

This study demonstrated that under-nutrition is an important public health issue for children aged 6-23 months in the study area, Jima Geneti District, Ethiopia. The prevalence of childhood under-nutrition (underweight, stunting and wasting) is patterned by various factors such wealth index, food insecurity, birth order, antenatal care visit, wild edible food consumption, dietary diversity score and child sickness. Thus, nutritional programs with effective multi-sectoral approaches might be designed and should be prioritized for tackling childhood under nutrition in the study area particularly and in the zone at large level. A joint effort by the government and nongovernment organizations is necessary to improve the childhood nutritional status in the communities.

pWollega University, College of Health Sciences. A formal letter of permission was written to Regional Health Office, Horro Guduru Wollega Zonal Health Department and to each selected kebele administration. After explaining the purpose of the study, verbal consent was obtained from each study participant. Participants were informed that participation is on voluntary basis. Personal identifiers were not included in the questionnaires to ensure participants’ confidentiality. Nutrition education regarding dietary diversity and their sources were given by the data collectors for households with malnourished children during the survey.

The authors would like to thank their Almighty God for giving them strength, indispensable grace and sustenance during the conducting of this research work. The authors would also like to thank the Wollega University, respondents, data collectors, supervisors, and district health office of the Jima Geneti district.

TY conceptualized, collected data, study designed, analyzed, interpreted and edited the manuscript.

The author declared that there was no potential conflicts of interest for this work.

The ethical approval was obtained from the Department of Food and Nutritional Sciences, Wollega University. The purpose of the study was also explained to the study participants and written consent was taken. The responses were kept confidential by coding.

The funding source of this work was Wollega University, Research and Innovation Technology.

[Cross ref] [PubMed] [Google scholar]

[Cross ref] [PubMed] [Google scholar]

Citation: Yazew T. Are Dietary Diversity and Food Insecurity Associated with Nutritional Status of Children in Western Oromia, Ethiopia? J Biol Today's World, 2022, 11(1), 001-005.

Received: 07-Jan-2022, Manuscript No. JBTW-21-34396; Editor assigned: 10-Jan-2022, Pre QC No. JBTW-21-34396(PQ); Reviewed: 24-Jan-2022, QC No. JBTW-21-34396; Revised: 29-Jan-2022, Manuscript No. JBTW-21-34396(R); Published: 08-Feb-2022, DOI: 10.35248/2322-3308-11.2.002

Copyright: © 2022 Yazew T. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.