Research Article - (2019) Volume 11, Issue 1

Marijuana (Cannabis) is considered the most commonly used illegal psychoactive drug in the world. Despite being regarded as a "soft" drug by experts for a long time, research has demonstrated that there are adverse addictive and psychiatric effects related to its use. Numerous elements are attributed with the mounting complications associated with the use of Cannabis, which include a gradual evolution in the proportions between tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC) and cannabidiol (CBD), the two major chemical compounds contained in Marijuana. This gradual evolution has been towards higher proportions of Δ9-THC. In the recent past, there has been an emergence of smokable synthetic herbal products that contain synthetic cannabinoids (SCs) in what appears to be a new trend in the landscape of psychoactive substances use. The uptake of these SCs has progressed rapidly among individuals who frequently use Cannabis owing to comparable psychoactive effects in SCs to Cannabis. Nevertheless, their pharmacological properties and composition make them dangerous elements. This paper investigates how synthetic marijuana (K2) mimics the effects of the naturally occurring chemical found in Δ9-THC.

Cannabidiol, Cannabis, Marijuana, Synthetic cannabinoids, Synthetic marijuana, Tetrahydrocannabinol

Cannabis also commonly referred to as marijuana among other names is a plant that contains psychoactive properties, with scientists claiming to have found more than 500 elements, among them 104 cannabinoids [1]. Among the multiple cannabinoids found in the substance, two have been the subject of multiple research studies owing to their chemical composition said to have medicinal qualities: Cannabidiol (CBD) and tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC). The potency of Cannabis is mainly assessed according to the concentration levels of Δ9-THC in any given sample. Δ9-THC is said to be the main psychoactive cannabinoid in marijuana. The negative effects associated with regular or acute use of Cannabis are directly linked to the concentration levels of Δ9- TCH in the consumed product. In the recent past, research studies have shown that levels of CBD equally have significant value with regard to the overall effects on the user. Research by Niesink and van Laar [2], indicates that CBD might protect individuals against various harmful psychological effects from the chemical compound Δ9-THC. They further claim that CBD has the capacity to aggravate at least a number of the negative impacts associated with Δ9-THC.

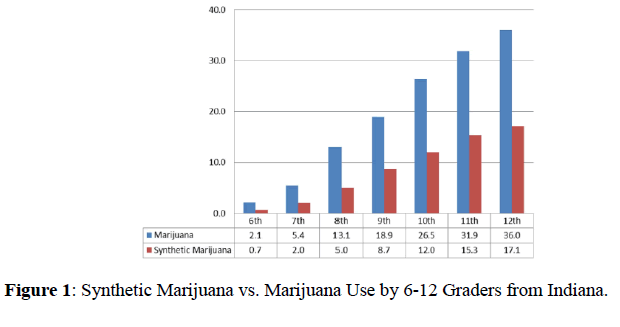

Synthetic cannabinoids (SCs), many times denoted as “Synthetic Marijuana, Spice, Dark Matter, Fake Weed, Kronic, Magic Mojo, Moon Rocks, Aroma, Black Mamba” among other street names is a group of chemical compounds that result in the same effect to Δ9- THC when consumed [3]. Contrary to Cannabis, SCs are not derived naturally from plants; rather, the chemical compounds used in their manufacture are synthesized in vitro. Clayton, Lowry, et al.[4] contend that despite the effects of these SCs having comparable outcomes to the consumption of the natural compound Δ9-THC, they might be stronger and can lead to negative health outcomes rarely witnessed with Δ9-THC. Use of SCs has been increasing with increasing consumption rates of Cannabis as indicated in Figure 1 below among youth in Indiana. 12th-grade learners have the highest rates of consumption for both substances with rates of increase in consumption of the two increasing proportionately as one advances.

Figure 1. Synthetic Marijuana vs. Marijuana Use by 6-12 Graders from Indiana.

Reports obtained by the CDC from the US poison centers show increased negative effects emanating from the consumption of SCs. Law, Schier, et al.[5] report that from the collected data, confusion, vomiting, lethargy or drowsiness, tachycardia, and agitation were some of the commonly reported adverse health impacts of SCs use. Clayton Lowry, et al.[4] further report that death (through overdose, adverse reaction, or suicide), dependence, anxiety attacks, aggression, paranoia, psychosis, stroke, renal damage, permanent cardiovascular damage, and seizures are some of the severe effects associated with SCs use. The toxicity effects of SCs emanate from the amount, mixture, and type of the used product. In addition, SCs producers frequently change their formulas to evade regulation and detection, and as such, the experience of an SC user may fluctuate over time. There have been endless arguments regarding whether the effects of natural and synthetic marijuana are comparable, and if so to what degree.

There are many studies done on the subject relating to SCs. Given the circumstances and the nature of the subject, a desktop analysis (secondary analysis) was preferred first to lay the groundwork needed for further research if needed in the future. As such, many research articles, journals, research papers, and individual studies conducted in the past were reviewed. Databases such as the NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information), PMC, Science.gov, Mendeley, and PubMed were consulted while doing this research. To obtain relevant information relating to the paper, keywords such as "synthetic marijuana," "synthetic cannabinoids,” “tetrahydrocannabinol,” “Spice,” “Black Mamba,” and “K2” were used. The five major databases used for this research gave a total of 1,254 research articles that had one or multiple search terms as outlined above.

To obtain more relevant data, other search terms were included such as "effects" and "outcomes." Although many articles had valuable information, the search was restricted to material that was published within the past five years. A total of 14 articles published within the past five years were found to be most relevant with regard to this study. Four were omitted for having inconclusive data and one was discarded for being outside the scope of this study. Articles whose data has been included in this review are peerreviewed and the data contained within is recent and thus have been included in this analysis. This strategy has been preferred given the cost aspect and the intricacies involved in conducting primary research, particularly with logistical challenges and the technical aspect of analyzing samples collected during a normal primary research analysis.

Research by Fantegrossi, Moran, et al.[6], on the metabolism of K2 synthetic cannabinoids contrasted to Δ9-THC indicates that the administration of two synthetic cannabinoids compounds JWH-073 and JWH-018 produces the same “tetrad” effects in mice, although they noted that the two SCs compounds demonstrate greater reductions in absolute core temperatures when contrasted to Δ9-THC. The results of the various randomized studies documented in the research by Fantegrossi et al.[6], showed that besides efficacy, the potency of SCs needed to produce numerous effects additionally vary when contrasted to Δ9-THC. They note that their interactions with cannabinoid tetrad in mice showed a rank order potency of the observed SCs to be Δ9-THC

Fantegrossi et al.[6], randomized trial results with rodents suggested that high efficacy cannabinoids such as those found in SC products might show reinforcing effects in selfadministered procedures. The assessment of the drug reinforcing effects in this specific study was attained through drug-administration by using the IV channel. The researchers also found withdrawal signs following discontinuation of repetitive treatment using SCs. Nevertheless, a similar discontinuation process applied to Δ9-THC does not prompt spontaneous withdrawal signs. More significantly, strong withdrawal effects are prompted in lab animals repetitively injected with cannabinoid agonists. The researchers noted that the withdrawal symptoms are typified by a number of observable signs including scratching, rubbing, licking, mastication, hypolocomotion, piloerection, ptosis, body tremor, hunched posture, ataxia, front paw tremor, facial rubbing, head shakes, and wet dog shakes.

The research drug tests results between the two chemical compounds JWH-073 and JWH-018 in mice showed that co-administration leads to antagonistic, synergistic, or additive interactions depending on the drug dose ratio employed or the examined endpoint. The researchers found that more specifically, synergistic interactions between synthetic marijuana were seen for radioligand displacement from CB1 receptors, for analgesia, and Δ9-THC drug discrimination. As such, it is suggested that comparable synergistic impact occurring in SCs found in K2 products may enhance their relative potency for both adverse and subjective effects and result in adverse side effects commonly associated with the use of these drugs.[7]

In their analysis, Lafaye, Karila, et al.[1], found that SCs and marijuana have different pharmacological properties. They note that SCs have lipophilic molecules that are full agonists of both CBD1 and CBD2 receptors. The researchers further noted that their latent binding affinity for both CBD1 and CBD2 is stronger than that of Δ9-THC, therefore, resulting in much more visible psychoactive effects than those seen in the natural Cannabis. The researchers further noted that unlike marijuana, SCs have no CBD whatsoever. Marijuana contains CBD in changing concentrations. The researchers note that herbal formulations that contain smoked SC (Spice) mimic the psychoactive effects associated with the chemical Δ9-THC.

Based on multiple studies outlined in their literature review, Lafaye, Karila, et al.[1], found that owing to their pharmacological qualities, SCs may have more negative impacts than those observed with marijuana. Despite Δ9-THC and SCs having the same mechanism of action, their varied pharmacological elements, which include but not limited to the absence of CBD, higher efficacy, and higher affinity for CB1 and CB2 receptors result in different toxicological and physiological effects, particularly regarding the pro-psychotic effects. The authors note that the psychotogenic effects of SCs are more and more alarming, with a number of reports of people who have developed psychosis subsequent to their use surfacing with increased intensity. Similarly, Karila et al.[3] noted that a majority of the documented psychoactive effects of SCs are similar to those seen with Δ9-THC. The authors noted that social withdrawal, perceptual distortions, intensification of sensorial experiences, lethargy, sedation, talkativeness, facilitated laughter, and subjective symptoms of euphoria are effects often described and associated with SCs use. Scholars Pacher, Steffens, et al.[8] also found comparable cardiovascular effects of SCs use with marijuana, although SCs had higher risk effects than marijuana.

Gurney, Scott, et al.[9] outlined physical signs associated with SCs use, which include tachycardia, increased blood pressure, dry mouth, increased appetite, conjunctival hyperemia. Research results by Clayton, Lowry, et al.[4] indicated that the prevalence rates of a majority of risk behaviors in the domains of sexual health, mental health, and violence/injury were bigger among student users of SCs. Student users of SCs had a higher prevalence rate of cases associated with violence/injury than those who used marijuana. The researchers further noted that linear contrasts indicated that there was a higher likelihood of 3 of the violence/injury behaviors occurring in students who used SCs than those who used marijuana. Similarly, the researchers found that following their linear contrasts, all 7 of risk behaviors in relation to sex had a higher likelihood of occurring among learners who ever used SCs than learners who used marijuana Table 1.

| Study | Well-defined Study Group |

Sample Size |

Blinded Outcom e Assessor |

Well defined Outcome |

Welldefined Risk Estimatio n |

Adjustmen t important confounders |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clayton et al. |

Yes. Based on information provided by the authors, the described study group fits the original cohort and did not consist of a random sample. |

The sample size was 15,624 which was statistical ly sufficient |

Unclear if outcome assessor was blinded to the effects of Δâ¹-THC |

Yes. Methods of analysis were well described and the outcome clearly defined precisely and objectivel y. |

Yes. Data was weighted to account for oversampli ng of various sections of the population. |

Yes. Other Important measureme nt variables were taken into account. |

| Fantegrossi et al. |

No. This was a systematic review of multiple research studies. There was no specific study group. |

No. This was a systemati c review of multiple research studies. There was no sample specific for this particular paper. |

There were no outcome assessors as the study did not have a specific study group. |

Yes. This was an explorato ry research study. The outcomes were well defined as the results of each study were well outlined. |

No. This was a systematic review of multiple research studies. This was not applicable. |

No. This was a systematic review of multiple research studies. It is not clear if these were taken into account. |

| Gurney et al. |

No. This was a presentation of case reports including forensic cases, clinical, and mental health admissions. |

No. This was a review of multiple research studies. There was no specific sample for this particular paper. |

There were no outcome assessors as the review comprise d an assessme nt of multiple study groups. |

Yes. This was an explorato ry research study. The outcomes were well defined as the results of each study were well outlined. |

No. This was not applicable. |

No. It is not clear if these were taken into account. |

| Hervas | No. This was an exploratory research study. There was no empirical research as the study reviewed other studies. |

No. This was a review of multiple research studies. There was no specific sample for this particular paper. |

There were no outcome assessors as the review comprise d an assessme nt of multiple study groups. |

Yes. This was an explorato ry research study. The outcomes were well defined as the results of each study were well outlined. |

No. This was not applicable. |

No. It is not clear if these were taken into account. |

| Karila et al. |

No. This was an extensive literature search that comprised of multiple studies on many different study groups. |

No. This was a review of multiple research studies. There was no specific sample for this particular paper. |

There were no outcome assessors as the review comprise d an assessme nt of multiple study groups. |

Yes. This was an explorato ry literature review. The outcomes were well defined as the results of each study were well outlined. |

No. This was not applicable. |

No. It is not clear if these were taken into account in the different studies that were reviewed by the author. |

| Lafaye et al. |

Yes. Based on information provided by the authors, the described study group fits the original cohort and did not consist of a random sample. |

There was no specific sample. Multiple groups were assessed in the different studies incorpora te in this review. |

Unclear if outcome assessor was blinded to the effects of Δâ¹-THC |

Yes. Methods of analysis were well described and the outcome clearly defined precisely and objectivel y. |

No. This was not applicable. |

No. It is not clear if these were taken into account in the different studies that were reviewed by the authors. |

| Law et al. | No. This was a research analysis of specific data collected by the CDC. The groups described therein fit the cohort. |

No. There was no specific sample defined for this study. |

There were no outcome assessors as the review comprise d an assessme nt of available data. |

The outcomes were well defined as the assessme nt addressed the relative effects of THC. |

No. This was not applicable. |

No. It is not clear if these were taken into account. |

| Niesink et al. |

Yes. Based on information provided by the authors, the described study group fits the original cohort and did not consist of a random sample. |

The sample size was 1,295 which was statistical ly sufficient |

Unclear if outcome assessor was blinded to the effects of Δâ¹-THC |

Yes. Methods of analysis were well described and the outcome clearly defined precisely and objectivel y. |

No. This was a systematic review of multiple research studies. This was not applicable. |

No. It is not clear if these were taken into account. |

| Pacher et al. |

No. This was an extensive literature search that comprised of multiple studies on many different study groups. |

No. This was a review of multiple research studies. There was no specific sample for this particular paper. |

There were no outcome assessors as the review comprise d an assessme nt of multiple study groups. |

Yes. This was an explorato ry literature review. The outcomes were well defined as the results of each study were well outlined. |

No. This was not applicable. |

No. It is not clear if these were taken into account in the different studies that were reviewed by the author. |

Table 1: Association between heparin use and miscarriage in pregnant women previously diagnosed with thrombophilia.

There are a number of studies that have been done in relation to synthetic marijuana as outlined in this research. This study is beneficial because it contributes new evidence regarding the behavioral correlation and the effects of the use of SCs on the users when compared to effects on common marijuana users. In general, it has been observed that SCs are associated with high prevalence rates of risk behaviors that have been highlighted in this study. The effects of SCs use are more pronounced than they are for those who use marijuana only especially sexual risk behaviors and substance use behaviors. It is also important to highlight the addictive potential of SCs products.

Withdrawal and tolerance symptoms that result from the use of synthetic cannabinoids have been described in this research. Toxicity is dependent on the amounts mixture and the type of the product used. Some studies highlighted in this research have shown that synthetic cannabinoids have more adverse effects than Cannabis and in some instances; users are adversely affected psychologically to the point of committing suicide. This paper has synthesized information from different research papers and it has been demonstrated that SCs affect regular users more adversely than marijuana. Chemical compounds in SCs have similar effects as those seen with Δ9-THC, although they appear to be more pronounced in SCs.

The regulatory framework

Owing to the constantly changing chemical ingredients of Spice, it is not clear whether synthetic marijuana can be referred to as an illegal drug or legal incense. The question of legality many times results in confusion even among officials that deal with its specific regulation. Today, at one time it might be referred to as being illegal and in the next day, a fresh product hits the market with different but with a related chemical composition thus lies beyond the scope of currently existing laws. It has become impossible for lawmakers to keep up with the constantly changing topography of synthetic marijuana. The legal process takes a long time for any law to be made, and by the time it is published and subsequently ratified by the US Congress, the ingredients have changed multiple times, which becomes nearly impossible to control. Producers are taking full advantage of this situation while also exploiting other loopholes within the law-making framework. For instance, many synthetic marijuana products have labels that read “not for human consumption,” selling it under the pretense of incense. In some instances, Spice is made available in difference gas stations in the US selling under other product categories.

There are a number of efforts that have been initiated by the federal government to try and control the use of synthetic cannabinoids. In the year 2011, the Drug Enforcement Agency applied emergency protocols to provisionally restrict some of the elements that are found in Spice. Through a coordinated effort between government agencies, in 2012, President Obama signed into law the Synthetic Drug Abuse Prevention Act.[10] This law categorized a majority of psychoactive substances, which included synthetic cannabinoids under Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act, which is usually the most controlled and restricted classification of substances in the US.[11]

The chemical Δ9-THC is the main psychoactive cannabinoid in marijuana. It has been demonstrated that SCs have more pronounced adverse effects on users, which include withdrawal symptoms and psychosis. SCs are unregulated and the formulas keep on changing, which means users can have varied effects based on changes of the chemical composition of the substances. With the evidence of the many adverse effects that come as a result of use of SCs and the associated complications as outlined in this paper, there is need to have more clinical and epidemiological studies to investigate the risk factors related with the abuse of synthetic cannabinoids for purposes of integrating such information in the treatment and prevention programs.

Copyright:This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.