Review Article - (2022) Volume 4, Issue 2

Pharmacological agents currently available for the treatment of primary insomnia have demonstrated limited long-term efficacy and problematic side effects. The purpose of this review is to highlight the concerns surrounding the most widely used medications that are commonly prescribed for the management of primary insomnia, and to summarize the mechanism of action and beneficial effects of the orexin receptor antagonists suvorexant, lemborexant and daridorexant as alternative therapeutic interventions for the management of primary insomnia.

Insomnia • Sleep difficulties • Orexin receptor antagonists • Suvorexant • Lemborexant • Daridorexant • Treatment

Insomnia is most widely defined as a state of persistent difficulty initiating sleep, staying asleep and /or early awakening with inability to resume sleep. In primary insomnia sleep difficulties are not related to underlying medical conditions, or other sleep-wake disorders. The recurrence of the sleep difficulties are not adequately explained by an underlying psychological condition, and persist despite the adequate opportunity and circumstances for sleep. It is estimated that about onethird of the adult population experiences symptoms of insomnia, with 10%-15% reporting daytime impairments in important areas of functioning [1]. It is also estimated that between 6% and 10% of individuals with sleep difficulties would meet core criteria for primary insomnia disorder, making it the most common sleep disorder among sleep-wake disorders [2]. Insomnia as a disorder is quite different from a brief period of poor sleep, with far-reaching consequences to both physical and mental health. It is a persistent condition with a negative impact on many aspects of daily life, and could seriously affect interpersonal, vocational, academic, and social functioning.

The goal of treating insomnia is to improve sleep quality and quantity, as well as daytime functioning, while avoiding adverse events and nextmorning residual effects. The prevalence of insomnia is considerably higher in patients with chronic medical disorders and in those with comorbid psychiatric conditions, especially mood, anxiety, substance use, and stress-and trauma-related disorders. General clinical guidelines including those of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) recommend Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I) as the most appropriate evidence-based treatment for patients with insomnia [3,4]. CBT-I includes sleep hygiene education, cognitive therapy, relaxation techniques, environment stimulus control and implementation of sleeprestriction [5]. However, many patients with primary insomnia experience ongoing sleep difficulties despite adherence to the elements of CBT-I, and other patients are simply unable to practice the tenets of CBT-I consistently enough to achieve clinically noticeable effects thus, necessitating adjunctive pharmacological interventions [5].

The conventional pharmacological treatments of primary insomnia fall into four main categories which include certain Benzodiazepines (BZDs), and non-BZDs hypnotics, a low dose of the Tricyclic Antidepressant (TCA) doxepin, melatonin agonists and other off-label sedating or hypnotic agents [6]. The various medications that are usually prescribed for insomnia treatment and their U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved indications are outlined in (Table 1). The BZDs receptor agonist hypnotics include: clonazepam, diazepam, flurazepam, lorazepam, temazepam, and triazolam, which promote sleep by enhancing Gamma- Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) inhibitory effects [7]. The non-BZDs hypnotics, also known as the “Z”-drugs have 3 compounds that include eszopiclone, zaleplon, and zolpidem with alternate structures but similar mechanisms of action to their benzodiazepine counterparts, by acting on the Gamma- Amino Butyric Acid-A (GABAA) receptors [8]. These two classes of medications have generalized central nervous system depressant effects and are associated with problematic adverse events, such as hangover, development of tolerance, addiction, rebound insomnia, muscular atonia, inhibition of respiratory system, and cognitive dysfunction especially in patients with underlying medical conditions and the elderly [9,10]. The abrupt discontinuation of the BZDs is also associated with physical withdrawal symptoms, manifested by increased anxiety, neurological, and cognitive symptoms, as well as the possibility of withdrawal seizures. The exact mechanism of the TCA doxepin on sleep is unknown, but is thought to be related to its histamine H1 receptors antagonism [11]. Doxepin seems to vary in its effects on sleep initiation and maintenance and its use is associated with sedation, somnolence, nausea, and possible upper respiratory tract infections [12]. Additionally, as other Tricyclic Antidepressant TCAs doxepin overdose can be lethal. The melatonin agonists, such as ramelteon [13], and various over the counter melatonin agents induce sleep through activation of melatonin 1 and melatonin 2 receptors in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus [14,15]. Recently the FDA has issued warning about several over the counter melatonin products which include higher than the 5 mg recommended doses and could cause severe adverse effects including headache, dizziness , nausea and drowsiness. Other off-label medications which have not been FDA approved for the treatment of insomnia (but are used as alternative agents due to their sedating properties) include certain compounds with antihistaminic-like effects, such as diphenhydramine, hydroxyzine and doxylamine. Antidepressants such as trazodone, mirtazapine, amitriptyline and trimipramine [6] are also frequently utilized to leverage these same properties. The long-term efficacy of these off-label medications on insomnia is not well established and their adverse effect profile of sedation, motor incoordination and tolerance are considered undesirable by many patients. These various classes of medications for the treatment of insomnia are widely available and are frequently prescribe because they are commonly associated with limited and short-term efficacy and multiple problematic side effects. There is a need for exploring alternative agents with greater efficacy and more tolerable side effects such as the orexin receptor antagonists. This review will summarize the mechanism action and the beneficial effects of the orexin receptor antagonists in the management of primary insomnia.

Table 1. Medications Usually Prescribed for Insomnia Treatment.

| Class | Generic (Brand) | Usual Starting Dose (mg)a | FDA Indication for Insomnia |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antihistamines | Diphenhydramine (Generic) | 25-50 | None-used off-label |

| Promethazine (Phenergan) | 25-50 | None-used off-label | |

| Antidepressants | Amitriptyline (generic) | Oct-50 | None-used off-label |

| Docepin (Silenor, generic) | 10-50 (doxepin); 6 (Silenor) | Silenor is indicated for treatment of insomnia due to sleep maintenance; generic docepin is used off-label | |

| Trazodone (Oleptro, generic) | 50-100 | None-indicated for treatment of major depressive disorder | |

| Antiseizure Agent | Gabapentin (Neurontin, generic) | 300-600 (only at bedtime) | None- Neurotin is indictaed for the management of postherpetic neuralgia in adults, as adjunctive therapy in the treatment of partial seizures |

| Melatonin Receptor Agonist | Ramelton (Rozerem) | 8 | Insomnia (chronic or transient) due to sleep onset |

| Nonbenzodiazepines | Eszopiclone (Lunesta, generic) | 02-Mar | Insomnia |

| Zaleplon (Sonata, generic) | Oct-20 | Short-term treatment of insomnia | |

| Zolpidem (Amblen, Edluar, generic) | Women: 5; Men: 10 | Short-term treatment of insomnia | |

| Zolpidem (Intermezzo) | Women: 1.75; Men: 3.5 | Insomnia caused by middle-of-the-night awakening, followed by difficulty returning to sleep | |

| Zolpidem CR (Ambien CR) | Women: 1.75; Men: 1.25 | Insomnia due to sleep onset or sleep maintenance | |

| Benzodiazepines | Clonazepam (Klonopin, generic) | 01-Feb | None-indicated for seizure and panic |

| Diazepam (Valium, generic) | 10 | None- indicated for anxiety disorders, alcohol withdrawal, and relief of skeletal muscle spasm | |

| Flurazepam (Generic) | 15-30 | Difficulty falling asleep, frequent nocturnal awakenings, and/or early-morning awakenings | |

| Lorazepam (Ativan, generic) | 01-Feb | None-indicated for anxiety disorder and short term relief of anxiety associated with depressive symptoms | |

| Temazepam (Restoril, generic) | 15-30 | Short-term treatment of insomnia | |

| Triazolam (Halcion, generic) | 0.25-0.5 | Short-term treatment of insomnia could cause amnesia | |

| Muscle Relaxant | Carisoprodol (Soma, generic) | 350 | None-indicated in adults for relief of discomfort associated with acute, painful, musculoskeletal conditions |

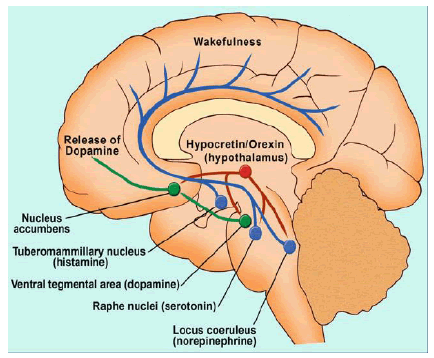

The orexin neuropeptides were discovered in 1998 and found to be produced by a small group of hypothalamic neurons whose actions are mediated by two receptors subtypes, Orexin-A (OXA) and Orexin B (OXB), also known as hypocretin-1 and hypocretin-2 or Orexin 1 Receptor (OX1R) and Orexin 2 Receptor (OX2R) [16,17]. They are located in the lateral, dorsomedial and peripheral lateral hypothalamus, as illustrated in (figure 1). Despite being highly localized, approximately 70,000 orexin neurons project widely throughout the brain and spinal cord, sending signals through the brainstem, cortical, and limbic regions, which activate the cholinergic and monoaminergic neural pathways of the ascending arousal system [12]. Their diffuse pattern of distribution correlates with their wide variety of functions in regulating appetite, metabolism, the reward system, stress, autonomic functions; and the most salient to this review, being the transition between wakefulness and sleep. The role of the orexinergic neurons in regulating the sleep-wake cycle led to the development of the orexin receptor antagonists as a new class of pharmacological agents for the treatment of insomnia. There are three orexin receptor antagonists: suvorexant, lemborexant and daridorexant. Suvorexant (Belsomra ®) was approved by the FDA in 2014 [18], lemborexant (Dayvigo®) was approved by the FDA in 2019 for the treatment of insomnia [19]. On January 2022, the FDA approved daridorexant (Quviviq®) to treat insomnia in adults. It is expected to be available for use in May 2022.

Figure 1: Orexin Neurons Location

Mechanism of action

Suvorexant is a Dual Orexin Receptor Agonist (DORA) that binds respectively to both OX1R and OX2R receptors and inhibits the activation of the arousal system, thus, facilitating sleep induction and maintenance, and thereby inactivating wakefulness [20].

Pharmacokinetics

Suvorexant is available as an immediate-release tablet with pharmacokinetic properties that potentiate onset and maintenance [21]. It is primarily metabolized through the Cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A pathway, with limited contribution by CYP2C19, it has no active metabolites, and its blood level and risk of side effects is higher with the concomitant use of CYP3A inhibitors [22]. It should not be administered with other strong CYP3A inhibitors. The initial dosage should be reduced when taken with moderate CYP3A inhibitors [21,22]. Concomitant use of strong CYP3A inducers can result in a low suvorexant level and reduced efficacy [21- 23]. The elimination half-life of suvorexant is approximately 12 hours, reaching a steady state in approximately 3 days [21]. Due to its moderately long half-life, it could be associated with residual morning sleepiness and somnolence which could impair daily functioning; however, this impairment could be minimized by using the lower dosage and by not exceeding the recommended dose [24]. Elimination is approximately two-thirds through feces and one-third in the urine [16]. Suvorexant metabolism differs in males and females and can be affected by the body mass index. Females and overweight individuals may require lower dosage [21-25].

Dosing

The recommended starting dose of suvorexant is 10 mg within 30 minutes of initiating sleep and of at least 7 hours remaining before awakening time. If the 10 mg dose is well tolerated, the dose may be increased to a maximum of 20 mg if neede d for sleep induction [26].

Adverse effects

Compared to those receiving placebo, patients receiving suvorexant were more likely to report fatigue, abnormal dreams, dry mouth, daytime sleepiness, and somnolence [27]. Impaired driving, suicidal ideation, sleep paralysis, hypnagogic/hypnopompic hallucinations, and cataplexy-like symptoms, although rare can still occur in some patients [28,29].

Contraindication

Although suvorexant was not evaluated in patients with narcolepsy, it might precipitate a spectrum of symptoms in patients with narcolepsy such as excessive sleepiness, cataplexy, hypnagogic hallucinations, and sleep paralysis. As such it is contraindicated in patients with narcolepsy [29].

Clinical considerations

The FDA categorized suvorexant as a Schedule IV controlled substance. Although there is no evidence of physiological dependence or withdrawal symptoms with suvorexant, it could carry a low risk for misuse and abuse potential [30]. There are no specific guidelines about the duration of treatment with suvorexant use, and it has not been associated withdrawal symptoms upon its discontinuation. Clinicians prescribing it for the maintenance treatment of insomnia need to inform their patients about its residual daytime sedation and somnolence and its potential for impairing driving or other activities that require full mental alertness, especially when prescribed above the 20 mg dosage.

Mechanism of action

Lemborexant is a Dual Orexin Receptor Agonist (DORA) that exerts its effects by reversible competitive binding, and thus inhibiting, the wakefulness effects of orexin on OX1R and OX2R receptors, with a stronger affinity for OX2R [31].

Pharmacokinetics

Lemborexant is available in immediate-release tablets with a peak concentration time of approximately 1 to 3 hours after ingestion. Its intake following a high-fat and high-calorie meal could delay its absorption and decrease its plasma concentration [19]. The elimination half-life of lemborexant is 17 hours to 19 hours, it is excreted in feces (57%) and to a lesser extent urine (29%) and it is primarily metabolized through the cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 pathway, and to a lesser extent through CYP3A5 [32]. Concomitant use with moderate or strong CYP3A inhibitors or inducers should be avoided, while use with weak CYP3A inhibitors should be limited to the 5mg dose of lemborexant [33]. The use of lemborexant with alcohol could lead to increased impairment in postural stability and memory, due to the direct effects of alcohol in addition to alcohol effects on increasing lemborexant levels and as such patients receiving lemborexant are encouraged to void alcohol use [34].

Dosing

Lemborexant is administered orally in doses of either 5 mg or 10 mg immediately before bedtime and of at least 7 hours remaining before awakening time to prevent impairment in alertness upon awaking. The maximum recommended clinical dose of lemborexant should not exceed 10 mg [35].

Adverse effects

The most common adverse effects are somnolence or fatigue. Headache, nightmares, or abnormal dreams also could occur [19,36].

Contraindication

Narcolepsy is the only contraindication to the use of lemborexant [19]. Narcolepsy is associated with a decrease in the orexin producing neurons in the hypothalamus, presumably causing the excessive sleepiness, sleep paralysis, hypnagogic hallucinations, and cataplexy characteristic of the disorder. Hypothetically, an orexin antagonist medication could exacerbate these symptoms [19,36].

Clinical considerations

Lemborexant is classified as Schedule IV controlled substances and has a low potential for abuse and dependence [34]. Possible impairment in alertness and motor coordination, especially with the 10mg dose, could affect next-morning driving especially in sensitive individuals [35] Caution is also advised with doses above 5mg in patients aged 65 years and older due to possible increased somnolence and a higher risk of falls [19].

Daridorexant

At the time of writing this review, and on January 2022, the FDA approved daridorexant (Quviviq®) to treat insomnia in adults. It is expected to be available for use in May 2022. In clinical trials daridorexant seems to be well tolerated with a favourable safety profile in adult and elderly patients. It’s reported adverse effects included headache, somnolence, fatigue, dizziness, and nausea [37]. There was no excess of morning sleepiness, as assessed by the morning Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), even at 50mg [37]. The incidence of somnolence was low and did not increase with daridorexant 50 mg compared to placebo [37]. The incidence of adverse events associated with orexin deficiency in individuals with narcolepsy, was low, with isolated cases of sleep paralysis or hallucinations in the daridorexant treatment groups [37].

Several nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic interventions are currently available for treatment of the chronic disabling effects of primary insomnia. Among the nonpharmacologic interventions, CBT-I is recommended as first line treatment intervention. Individuals with persistent and chronic primary insomnia may require adjunctive pharmacologic interventions. While agents including Benzodiazepines (BZD), and the nonbenzodiazepines ‘Z’-drugs, or ramelteon, melatonin, doxepin, and other sedative and hypnotic agents are commonly used to improve sleep, these compounds have consistently demonstrated limited long term efficacy and problematic side effects. The discovery of the orexin signalling pathway and its role in sleep/wake maintenance has led to the development of the orexin antagonist agents such as suvorexant, lemborexant and daridorexant. This review summarized the mechanism of action and the beneficial effects of these new therapeutic agents. Orexin antagonists have demonstrated promise as alternative treatment modality for the management of chronic primary insomnia in those individuals who have not responded to the various conventional nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic treatment interventions. Additional studies are needed to evaluate the efficacy of combining the newly available orexin antagonists with nonpharmacologic treatments, particularly in individuals with cooccurring medical and psychiatric conditions.

The authors express their thankfulness and gratitude to their family, friends and colleagues for their support and encouragements.

The materials described in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the VA Central California Health Care System, UCSF Fresno Medical Education Program, California, or the Michael E DeBakey VA Medical Centre, Houston, Texas. Neither author has any conflicts of interest to report.

Citation: Khouzam HR, Jackson S. Orexin Receptor Antagonists: Alternative Treatment of Primary Insomnia. Neurol Neurorehabilit. 2022, 4(2), 016-019.

Received: 18-Apr-2022, Manuscript No. NNR-22-61500; Editor assigned: 25-Apr-2022, Pre QC No. NNR-22-61500 (PQ); Reviewed: 29-Apr-2022, QC No. NNR- 22-61500 (Q); Revised: 05-May-2022, Manuscript No. NNR-22-61500(R); Published: 10-May-2022, DOI: 10.37532/22.4.2.16-19

Copyright: 2022 Khouzam HR, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.