Rapid Communication - (2015) Volume 6, Issue 5

Until recently, there was little understanding of the exact pathophysiology and treatment choices for stroke patients with Pseudobulbar affect (PBA). PBA is typically characterized by outbursts or uncontrollable laughing or crying and in the majority of patients, the outbursts being involuntary and incompatible with the patients’ emotional state. PBA is a behavioral syndrome reported to be displayed in 28-52% of stroke patients with first or multiple strokes, and incidence may be higher in patients who have had prior stroke events, and higher in females. There is typically involvement of glutaminergic, serotoninergic and dopaminergic neuronal circuits of the cortico-limbic-subcorticothalamic-pontocerebellar network. PBA is now understood to be a disinhibition syndrome in which specific pathways involving serotonin and glutamate are disrupted or modulated causing reduced cortical inhibition of a cerebellar/brainstem-situated “emotional” laughing or crying focal center. Stroke-induced disruption of one or more neuronal pathway circuits may “disinhibit” voluntary laughing and crying making the process involuntary. With a “new” treatment currently being marketed to treat PBA patients, this article will delve into the neurological and physiological basis for PBA in stroke, and review progress with the diagnosis and treatment of PBA.

Keywords: PBA; Dysregulation; Treatment; Depression; Laughing; Brainstem; Cerebellum; Mania; Robotripping; Antidepressants.

Unpredictable and highly exaggerated episodes of crying or laughing that are dramatically incongruent with the context of a stroke patient’s situation are now commonly known as pseudobulbar affect (PBA). PBA has been referred to as pathological laughing and crying (PLC), emotional liability, emotional dysregulation, involuntary emotional expression disorder, and even emotional incontinence (EI). PBA is an emotional disturbance that occurs in patients secondary to a stroke or multiple strokes. In many patients, the episodes cannot be easily controlled voluntarily. Key characteristics of PBA are that episodes can last from seconds to many minutes, episodes are not stimulated by a specific situation, conversely, PBA occurs in situations making crying or laughing awkward, causing the patient to be agitated and embarrassed.

Statistics for PBA vary somewhat between source and depending on the year of the publication [1], but there appears to be an increase in prevalence due to the increased diagnosis of the condition. In the PBA Registry Series (i.e., PRISM) [1], Brooks et al. estimated that up to 2 million people have PBA based upon screening using an online survey; the results were questionable because it was deemed self-diagnosis and results were not independently confirmed. Moreover, there was no other disease condition associated with PBA diagnosis. A survey of literature from 1993-present [2-6] indicates that up to 52% of stroke patients may have PBA and that a greater percentage of women report and/or have PBA compared to men, suggesting a significant gender difference. In the analysis by Colamonico et al. [7], House et al. [8], and Kim [9], 11-34% of stroke patients were afflicted with PBA based upon results from various diagnostic scales. There may be a correlation with depressive state of the stroke patient and the incidence of PBA [8,10]. Therefore, a significant population of stroke patients needs a treatment for PBA.

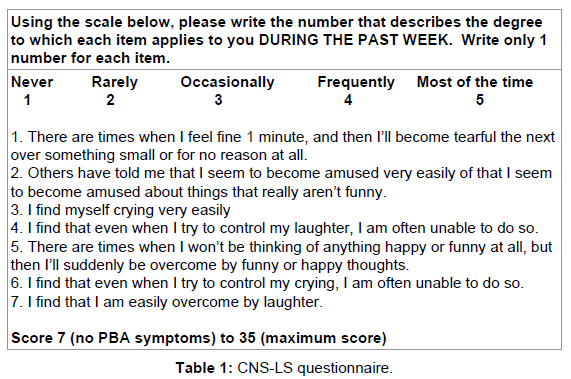

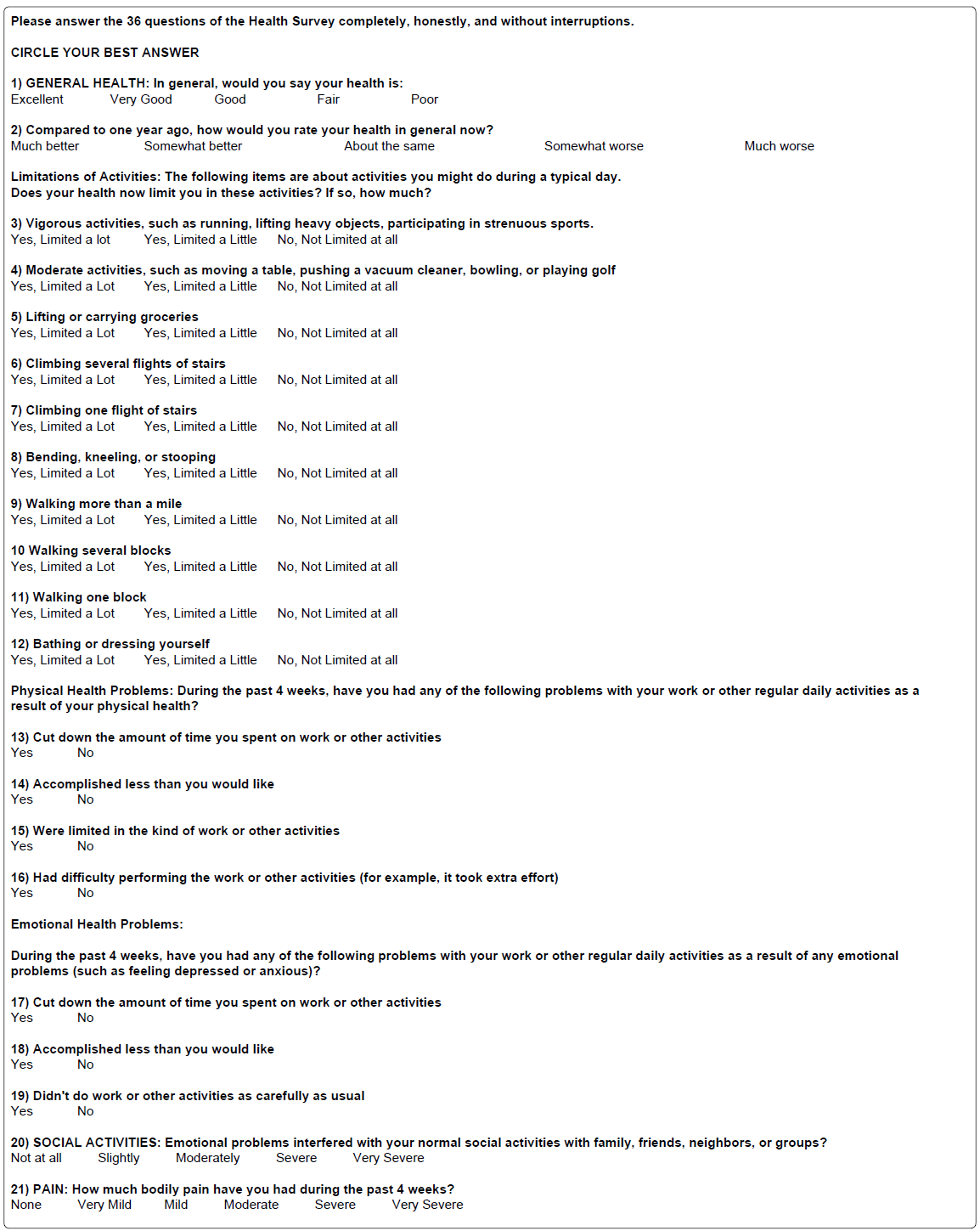

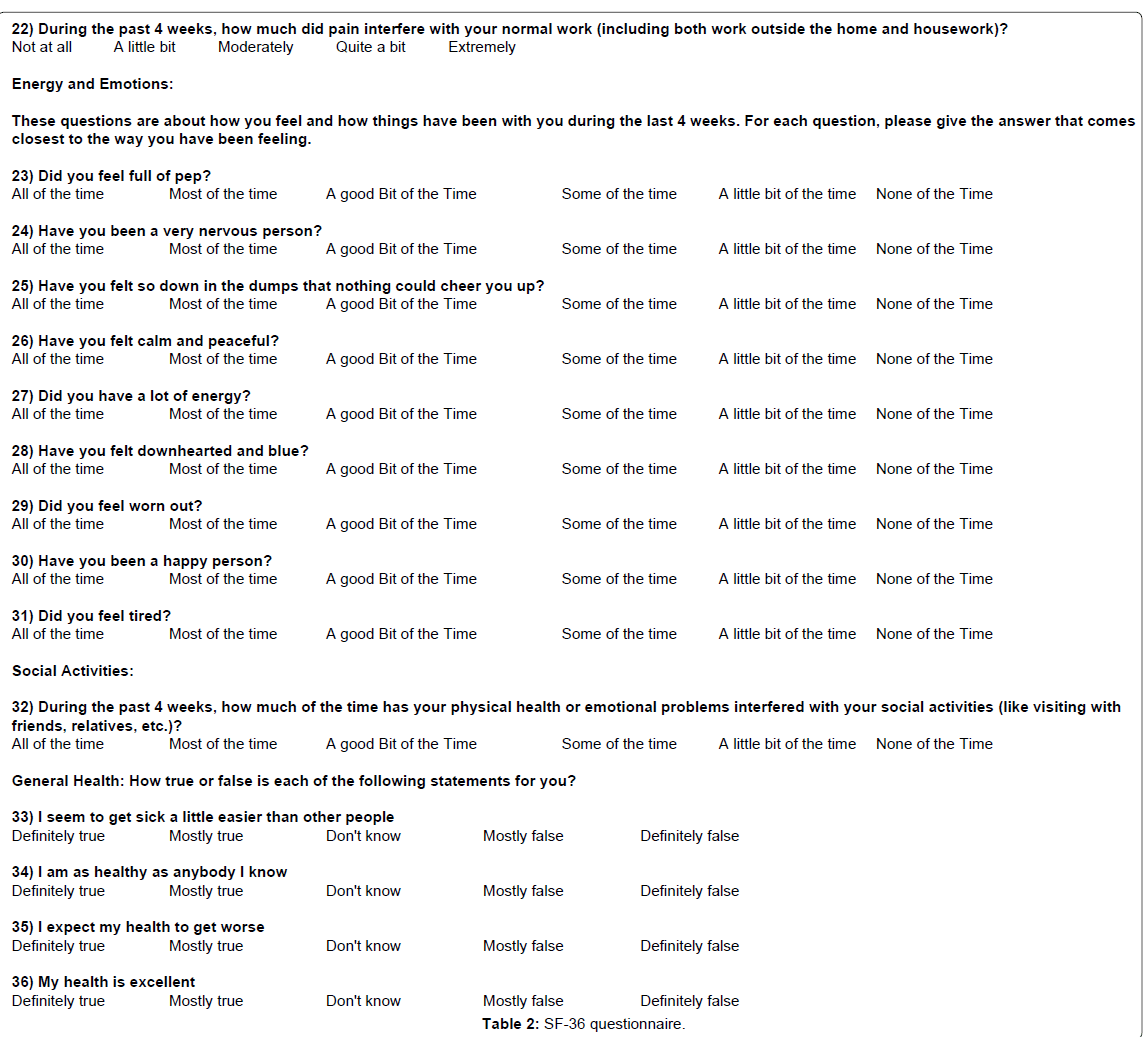

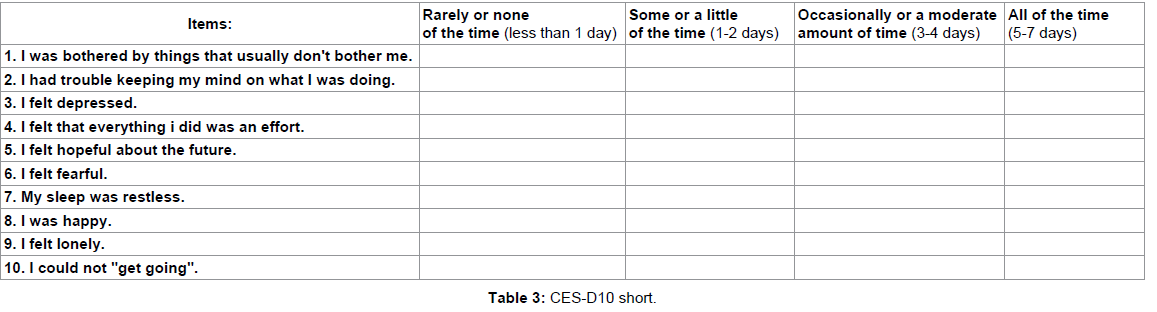

Currently, there are at least 5 useful and different rating scales performed either by the patient or the caregiver to “diagnose” the condition PBA, some of which are useful for differential diagnosis. The most commonly used scales are described below and presented in (Tables 1-4):

(1) Center for Neurologic Study lability scale (CNS-LS), a validated scale [11] with score 7 (no PBA symptoms) to 35 (maximum score) [Moore et al [11]] Example Form 1 (Table 1).

(2) 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36), a 36 question form that primarily rates quality of life and basic health inclusive of mental well-being with score 0, worst health to 100, best health [7,12,13] Example Form 2 (Table 2).

(3) Center for Epidemiologic Studies depression 10-item short form (CES-D10), a 10 question form primarily targeting depressive behavior with a score of 10 or greater considered depressed. Note, there is a CES-D20 version of the form that is more comprehensive and a cutoff score of 16 is indicative of significant depressive symptomatology. Example CES-D10 Form 3 (7) (Table 3).

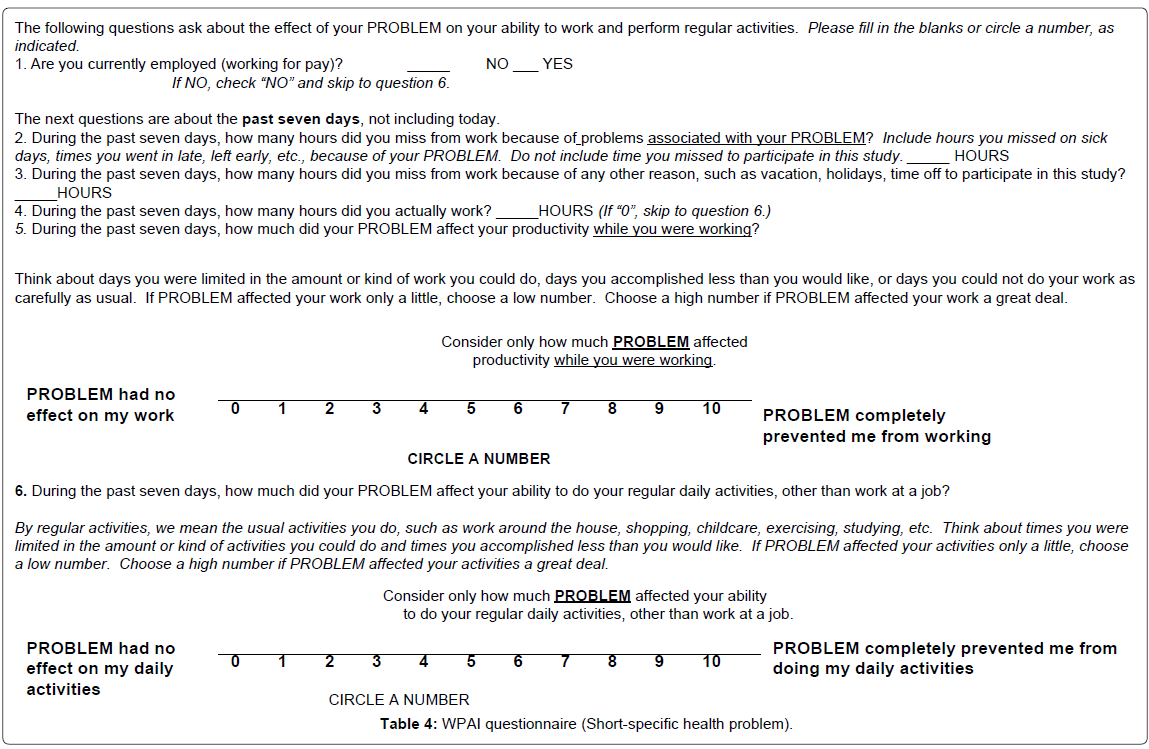

(4) Work productivity and activity impairment (WPAI) questionnaire correlated work productivity (i.e.: assessing impairments in paid work and activities) with extent of impairment. Example Form 4 (7) (Table 4).

(5) Visual analog scale quality of life quality of relationships (VAS QOL/QOR). The scale is particularly useful to determine the impact of PBA symptoms on QOL and QOR [7]; the higher the score the greater the negative impact of PBA on quality of life measures in the patient.

The recent articles by Colamonico et al. [7] and Brooks et al. [1] present a comprehensive overview and comparison of responses received from questionnaire takers using some of scales described above. The most consistent diagnosis of stroke patients with PBA resulted from the CNS-LS questionnaire, with use of the CES-D10 for diagnosis of PBA instead of depression, and it is clear that higher CNSLS scores will negatively impact VAS QOL scores (higher score).

Few stroke patient studies have documented and correlated the incidence of PBA with neuronal damage in specific brain regions. There is literature pertaining to PBA involvement of primary neurotransmitters pathways including disruption of glutamate and serotonin transmission: serotonin in the corticolimbic and/or cerebellar pathways may be involved in PBA, whereas widespread modulation of glutamate transmission would have an impact on PBA incidence.

This section will summarize known neuroanatomical changes synthesized from neurodegenerative disease patients with PBA to form a thesis. For example, Kim [14] studied a population of 25 patients presenting with first strokes and found that post-stroke emotional incontinence was associated with infarcts in the dorsal globus pallidus, primarily of serotonergic origin. In addition, PBA has been correlated with lesions in the frontal lobes and pathways descending to the brain stem, basilar pontine nucleus and to the cerebellum [15,16]. It is thought that the cerebellum neurotransmission, in particular corticopontinecerebellar circuits causes impaired cerebellar control of emotional responses. Ahmed and Simmons [17] have proposed that PBA is a disinhibition syndrome in which specific pathways involving serotonin and glutamate are disrupted. If there is reduced cortical inhibition of a brain stem situated “emotional” center related to laughing and crying, stroke-induced disruption of the pathway may “disinhibit” voluntary laughing and crying [15,16], making the process involuntary. Parvizi and colleagues [16] have termed loss of cortical-cerebellar input control of emotions “dysmetria” of emotional expression.

There may also be a sensory and motor component regulating emotions: the cerebellum acting as a gate controller over direct input from the motor cortex and frontal and temporal lobes. Thus, since many PBA patients have right frontal lobe lesions, and left frontal and temporal lesions [17], it is also possible that damage to frontotemporalsubcortical circuits may be involved in PBA. For example, the motor cortex circuit may be modulated by inhibitory input from the somatosensory cortex. A lesion in the cortex may reduce the inhibitory input resulting in disinhibition of the cerebellar-controlled “emotions”.

Brain mapping studies using diffusion-tensor magnetic resonance imaging (MRI/DTI) and electroencephalography (EEG) suggests that reduced serotonin and dopamine transmission and enhanced glutamate transmission are key components in the emotional dysregulation [18]. Thus, with this limited information, the hypothesized treatment for PBA would enhancing both serotonin and dopamine pathways and decreasing glutamate receptor stimulation.

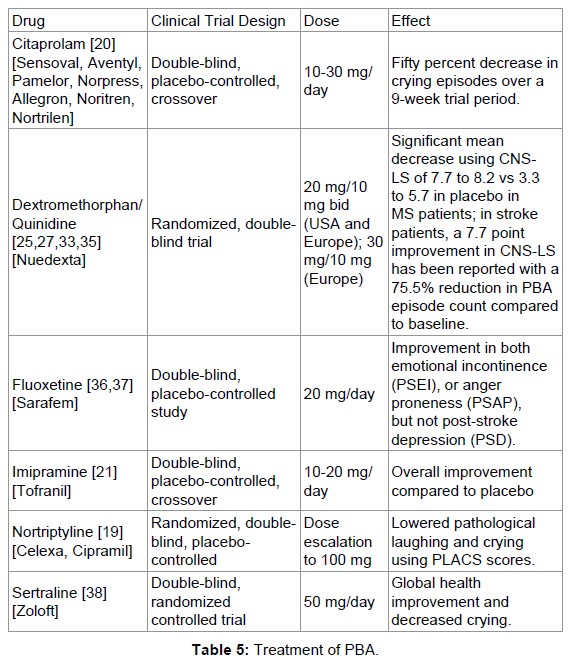

Pharmacological intervention to reduce the number of PBA episodes and improve QOL can be directed at dopamine, serotonin and glutamate receptors, enzymes involved in removing neurotransmitters from synapses (Table 5). For PBA, a series of clinical trials with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as fluoxetine, sertraline, and paroxetine have proven to be beneficial to the patient as have tricyclic antidepressants (TCA, i.e., nortriptyline); the efficacy of SSRI’s and TCA’s is related to the serotonergic function enhancing component of each drug. In stroke patients, in a clinical trial setting, nortriptyline [Sensoval, Aventyl, Pamelor, Norpress, Allegron, Noritren and Nortrilen] [19], citalopram [Celexa, Cipramil] [20] and imipramine [Tofranil] [21] were found to be effective, but these drugs were never FDA-approved for the treatment of PBA. Moreover, there are sporadic reports of selective noradrenergic reuptake inhibitors (duloxetine [Cymbalta], venlafaxine and roboxetine) having some efficacy to treat PBA [22-24]. This long series of drug remain as possible choices offlabel therapy choices for PBA patients who do not respond or fully respond to the current FDA-approved treatment (see below).

Glutamate antagonists, in particular the cough suppressant dextromethorphan [17,25,26], which can inhibit glutamate activity via the classical N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor as well as sigma 1 (σ1) receptors, but these activities are also related to toxicity (mania and robotripping) with excessive administration and overuse of the drug [26-32]. Drug metabolites also have potent activities at NMDA and σ receptors [25].

Surprisingly, the combination of dextromethorphan and quinidine (Nuedexta) is currently the only FDA-approved treatment for PBA. Nuedexta contains two different components; dextromethorphan hydrobromide to act on sigma-1 and NMDA receptors in the brain, and quinidine sulfate, a metabolic inhibitor (i.e.: a specific inhibitor of cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6)–dependent oxidative metabolism), and a class I antiarrhythmic agent [(by blocking the fast inward sodium current (Ina)] that enables dextromethorphan to reach therapeutic concentrations (see http://www.avanir.com/nuedexta). The proposed mechanism of action of the therapeutic does not seem to directly target dopamine and serotonin dysfunction in PDA, leaving new avenues open for PBA treatment using multi-drug combinations.

Clinical studies with Nuedexta in Multiple sclerosis patients demonstrate efficacy with a significant mean decrease of 7.7 to 8.2 vs 3.3 to 5.7 in placebo-treated patients using CNS-LS scores; the absolute benefit is 2.5-4.4 points as documented by Pioro et al. [33] and Panitch et al. [34]. In stroke patients, in PRISM II, a 7.7 point improvement in CNS-LS has been reported with a 75.5% reduction in PBA episodes compared to baseline [35].

PBA is due to the dysregulation of 3 main neurotransmitter pathways, dopamine, serotonin and glutamate, from the frontal cortical lobes through the cerebellum and brain stem, the corticolimbic- subcorticothalamic-ponto-cerebellar network. Stroke or infarct-mediated interruption of circuits projecting to the cerebellum and brainstem may result in disinhibition of well-controlled voluntary emotions, making them involuntary. With Nuedexta being FDA-approved as a treatment for PBA, and with only modest, but statistically significant efficacy of the drug combination, new treatment options targeting dopamine and serotonin, in addition to glutamate, should be pursued to provide stroke patients the best opportunity to improve QOL by reducing PBA episodes.