Research Article - (2023) Volume 9, Issue 2

In a physically-distanced world, citizens are obliged to stay enclosed by the four walls of their homes, medical professionals are bustling in hospitals filled with virus-infected patients and the government is addressing pressing matters day-to-day. This ‘new normal’ was brought about by a new, novel virus 2019-nCov that has swiftly landed to attack the world’s inhabitants has taken the life of 1.65 M humans.

Magnifying to a region 7 province called Cebu, one amongst the many affected provinces has 24,492 total COVID-19 cases, based on December 2020, the highest in the Philippines. Cebu is the second most populated province in the Philippines and the most populated province in Central Visayas. It comprises six cities: Cebu city, Mandaue city, Lapu Lapu city, Toledo city, Danao city and Talisay city (Philippine statistics authority, 2013. During the pandemic, its two highly urbanized cities, Cebu city and Mandaue city, contained the most COVID-19 cases in the province. Similar to cities such as Manila, it has been difficult to contain Cebu’s COVID-19 outbreak. As cases continue to rise, lockdowns are strengthened and the future is blurred by COVID-19’s tumultuous road.

This paper aims to analyze the response and outcomes of Cebu’s efforts through the use of statistics from March to December and interview responses from the Cebu city Mayor Edgar Labella, medical professionals and citizens. Moreover, this paper’s focus is to compare the protocols and outcomes of two cities, Cebu city and Mandaue, as these are Cebu’s two highly urbanized cities and its COVID-19 epicenter. Based on the analysis of data and efforts, the paper will then provide recommendations regarding Cebu’s COVID-19 response in moving forward with the new normal.

Health • Economics • COVID 19 pandemic • Virusinfected patients • Urbanized cities

COVID-19 situation

News about the coronavirus outbreak felt so far out of reach since it began in Wuhan, China. However, because quarantine protocols were not yet implemented and planes were still coming in and out of the country, the first COVID-19 case was confirmed on January 30, 2020 after a 38-year old woman from Wuhan arrived in the Philippines.

Two days later, the first COVID-19 death in the Philippines was declared [1-3]. Although the first confirmed case was in January, the first new confirmed cases and local transmission were announced on March 9, and a state of calamity was declared when Quezon city was the first to be placed on lockdown on March 13. Overseas Filipino Workers (OFW) have taken jobs worldwide including China. “More than 230,000 migrant Filipinos often referred to as Overseas Filipino Workers (OFW) are also working in China particularly Hong Kong and Macau as household workers.” This put the Philippines at a greater risk of experiencing an influx of positive cases compared to other countries [4].

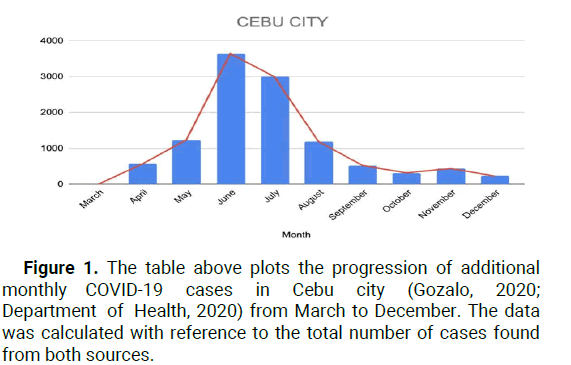

As cases started to increase, the first confirmed cases were first declared in Cebu on March 13. On March 25, 2020, Cebu Governor Gwen Garcia announced that Cebu will be placed on Enhanced Community Quarantine (ECQ) to prevent the spread of the coronavirus that has already arrived in Manila [5]. Two days after, Garcia held an emergency meeting to allow local government units to request and access funds to facilitate the move towards suppressing the virus. On this day, 1,000 necessary hospital equipment such as personal protective equipment, goggles, masks and protective suits were also distributed to Cebu City [6]. The table above plots the progression of additional monthly COVID-19 cases in Cebu City from March to December. The data was calculated with reference to the total number of cases found from both sources.

Cebu city

the 16th of March, Cebu city Mayor Edgar Labella placed Cebu city on Enhanced Community Quarantine (ECQ) until April 14 [7]. During the press conference, Labella said, “We don’t have yet a confirmed positive case. But it is better to be preemptive and precautionary rather than reactive”. By March 20, international flights were banned from entering Cebu, however, cargo in airports and seaports were still permitted. As of March 26, ten days after ECQ implementation, Cebu city had seven potential COVID-19 cases. Because of the abrupt arrival of the virus, swab tests were conducted in Vicente Sotto memorial medical center and sent to research institute of tropical medicine in Muntinlupa city for confirmatory tests (Figure 1) [8].

Figure 1: The table above plots the progression of additional monthly COVID-19 cases in Cebu city (Gozalo, 2020; Department of Health, 2020) from March to December. The data was calculated with reference to the total number of cases found from both sources.

Two days after Governor Garcia placed Cebu under ECQ, Cebu city received 19 confirmed cases: 16 hospitalized, two deceased and one recovered.

DOH 7 said that they are expecting a rise in cases once their additional laboratory is operational. At the beginning of April, the 19 confirmed cases increased to 25. By April 13, no cases were reported as positive, and the total number of confirmed cases stood at 25 [9]. Five days after the 13th, two more cases were confirmed from Sitio Zapatera in Barangay Luz and Barangay Hipodromo, as said by Mayor Labella. A massive swab testing was done in Sitio Zapatera resulting in 136 total confirmed COVID cases in that area. A Cebu city jail facility in Barangay Kalunasan reported 114 inmates and 13 jail staff tested positive and had 20 more additional cases. By the end of April, Cebu City secured a total of 567 confirmed cases. Only three days in on May, Cebu city recorded approximately 364 new confirmed cases: 31 new COVID-19 cases were reported by the Cebu city health department and 333 by the Cebu city Jail. Cebu city accounted for 910 COVID cases which is a bulk of Cebu’s 1,084 COVID-19 cases. On the 17th, 21 new cases were added coming from nine barangays (Chua, 2020). Cebu City recorded a total of 1,513 COVID-19 cases by the 17th [10].

Cebu City still remained under ECQ since the beginning of quarantine. However, the number of positive COVID-19 cases continued to grow as 18 new cases were recorded three days after the 21-cases. These new cases were no longer from Sitio Zapatera in Barangay Luz as they have been lifted from lockdown on this day [11]. Cebu City’s total number of cases now stood at 1,782, and ECQ still remained until the end of May, By the end of May, Metro Cebu had prepared to shift from ECQ to Modified ECQ (MECQ) where businesses are permitted to open by June 1 to June 15 [12]. Placing Cebu City under MECQ would not mandate citizens to participate in COVID-19 testing rather it would only encourage them. Mayor Edgar Labella said, through spokesman Rey Gaelon, that Cebu City is now ready to transition to MECQ because “the city had already issued guidelines under the MECQ risk classification but it was overtaken by the (Inter-Agency Task Force on Emerging Infectious Diseases) or IATF(-ED) resolution placing us again to ECQ”. University of the Philippines (UP) researchers, however, recommended otherwise. In the researchers’ Post-ECQ report, it was projected that COVID-19 cases would still be very high in areas, specifically NCR and Cebu City. They recommended that the quarantine be extended to continue crucial restrictions and to avoid further worsening of the coronavirus spread. As of May 24, a total of 1,869 cases were reported by Cebu city [13].

The last two cities to transition to looser quarantine measures, such as MECQ and General Community Quarantine (GCQ), are Cebu city and Mandaue city. As said in the previous paragraph, Cebu city looked to transition to MECQ while Mandaue city to GCQ. Resolution No. 40 issued by IATF-EID (Inter-Agency Task Force for the Management of Emerging Infectious Diseases) on May 27 was to place Cebu city under MECQ and classifying it as a high-risk HUC (Highly Urbanized City) [14]. However, two days after this announcement, IATF-EID issued Resolution No. 41 as a replacement as per request of Mayor Labella which allowed Cebu city to join Mandaue city along with other cities such as Mandaue city and Metro Manila in GCQ, which is much farther than what the UP researchers recommended. Cebu city’s first day of GCQ recorded 85 additional COVID-19 cases. Galeon, Mayor Labella’s spokesperson, reminded citizens “to stay vigilant and follow health protocols even if several quarantine measures had been eased following the declaration of GCQ” [15]. On the 9th of June, Cebu city had a total of 2,988 confirmed COVID-19 cases. About only two weeks after the 1,869 cases on May 24, Cebu city had recorded approximately 1,000 more confirmed cases. The day after, June 10, the city recorded 101 additional cases, exceeding the 3,000 count with 3,089 total coronavirus cases. After 16 days of the city’s GCQ transition, Cebu city converted back to ECQ until June 30 after the surge of COVID-19 cases and widespread local transmission at the start of its GCQ. Cebu city now emerged as Philippines’ COVID-19 “epicenter” or “hotspot” holding a total of 3,361 total coronavirus cases as of June 12 [16].

By the end of June, Cebu city hit its highest number of single-day additional COVID-19 cases with 353 as the count. The city ended the month with a total case count of 5,456 with 69 deaths and 2,723 recoveries, including 69 employees of the local city government. Succeeding the sudden spike of COVID-19 cases, President Rodrigo Duterte extended Cebu City’s ECQ to July 15 [17]. The President expressed his opinion on the situation: "Kamong mga Cebuano, ayaw mo kasuko nako ginabadlong ta mo. Suberbiyo mo eh, dili tanan. pero naa gud sa inyo (You Cebuanos, don't be angry with me for scolding you. You're so stubborn, not all. But there are some of you who are)". Talk about the continued rise of COVID-19 cases in the city circulated at the start of June [18]. From Inquirer, Mayor Labella said, “the continued rise in COVID-19 cases in his city should not be a surprise since it was the only city where the local government was conducting massive testing among the people”. He also stated that two illegal settlements Barangay Luz and Mambaling contributed a largeproportion of June’s 4,700 cases [19]. Houses that inhabited these barangays are only “separated by a wall,” making it difficult for its inhabitants to ensure adherence to safety protocols. By the end of Cebu city’s reversion to ECQ, they transitioned to MECQ with careful watch from the national government due to the sudden spike of cases. On July 19, Cebu city was able to recover nearly a total of 4,500 COVID-19 patients from June’s 2,723 total recoveries.

After the surge of cases at the beginning of June, the city had a hint of optimism and hope as additional cases slowed down on month’s end. Cebu city stood at 8,813 total confirmed coronavirus cases with 5,075 total recoveries. Finally, the city’s quarantine measures eased to GCQ by the end of July. The beginning of August looked much lighter than the previous months as cases started decreasing. By August 6, 13 infections were recorded compared to the 100 to 200 cases of the months prior. Based on the line graph and the DOH-7 data, a downward trend was finally projected. August’s first week reported only 153 cases which is significantly fewer than the beginning of the pandemic. DOH-7 expresses that the additional cases are because of “more accurate data collection and validation efforts”. Cebu city continued to be under GCQ, and the low number of cases convinced the Department of Health-Central Visayas (DOH 7) that the city is on the route of flattening the curve.

According to DOH-7 spokesperson Loreche, August daily cases stood at an average of 27.4. Health experts warned office workers to be extra cautious and practice safety measures as most of these cases were recorded to be pertaining to this job. By the end of August, Cebu city recovered from July’s sudden massive spike holding less than 1,000 active cases. COVID-19 cases continued to stay at a low range for the rest of the year. However, in the month of November, there was another spike in cases which was misinterpreted as the “second wave” for the city. DOH-7 chief pathologist Mary Jean Loreche clarified that it was only a spike which later decreased in the following month. Although Cebu city’s June COVID-19 report and “new COVID-19 epicenter” label left many cities and even the President appalled, it only took the city a month to recover and flatten the curve. Macasero said the city was able to flatten the curve because of the 4 week-MECQ that eased the pressure that was put on the health sector and government. The prolonged and strict quarantine measures impacted the city greater than those who transitioned to looser quarantine measures too quickly. With this, the city focused on increasing the number of contact tracing teams and speeding up swab results to record and treat more COVID-19 positive patients. Free RT-PCR swab testing was made available to all residents, symptomatic or asymptomatic, in July showing the government’s priority to accommodate as many citizens as possible [20].

Mandaue city

As of the 17th of March, Mandaue city had 37 patients under investigation and 22 persons under monitoring. The next day, the city confirms its, and the Visayas’, first COVID-19 case who is a 65-year-old man. The patient did not travel outside of the country; he travelled to different cities, specifically Metro Manila and Mindanao. After its first confirmed case, Mandaue Mayor Jonas Cortes said that he implemented “a curfew, social distancing protocol as well as hygiene and sanitation initiatives”. The city ended the month of March with two confirmed cases. The month April remains low on coronavirus cases, with 17 additional cases for the whole month. One of these cases was an inmate from Mandaue city jail, who later on died in Vicente Sotto memorial medical center. However, in May, cases started to rise as Mandaue city jail reported 60 more cases. On the 16th of May, Mandaue city was placed under ECQ along with Cebu city. At month’s end, Mandaue city logs 259 total coronavirus case. June started off with 53 additional coronavirus cases from 7 barangays on June 13. The city stood at 401 total confirmed cases with 95 recoveries and seven deaths. By mid-June, Mandaue city’s ECQ quarantine restriction was eased to GCQ. While on GCQ, 35 new cases, including a 3-year-old boy, were added to the case tally. The city’s disaster risk reduction team then performed a decontamination and contact tracing in the city’s affected barangays.

The first of July already recorded 17 more cases who were policemen. Two weeks later, 28 more policemen tested positive for coronavirus. With the help of Red Cross Philippines, Mandaue City opened a molecular laboratory, the biggest in the Visayas, that was made available for testing to expand the testing capacity of the city on July 16, the same day as the 28-case augmentation. The laboratory is capable of performing simultaneous tests and providing test results after 48 hours which speeds up the entire COVID-19 processes. The Mandaue city jail was declared free of COVID-19 on July 20. However, as the month neared its end, 47 cases were added to the tally, making 1,834 its total case count in July, with its highest, 1,027 additional monthly COVID-19 cases. August’s first week came with good news as the city recorded a high recovery rate given a total number of 1,121 recoveries and 719 active cases. Five days later, 27 new positive cases were reported.

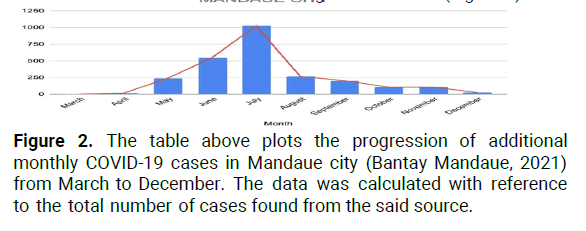

However, the number of active cases had been declining, and the number of recoveries had been increasing, making this month successful in recovering from July’s surge of additional cases. Mandaue City decided to disinfect public schools to be used as isolation centers. With the permission of the Department of Education (DepEd), nine public schools in the city were available to be used as isolation centers. The city logged 2,101 total number of coronavirus cases with 760 less additional cases than July’s and remained under GCQ until the end of August. Coronavirus cases continued to slowly decrease until the end of 2020. As shown in the graph, there was a two-monthplateau from October to November which placed the city under Modified General Enhanced Community Quarantine (MGCQ) in November until the end of the year. The city was able to flatten the curve because instead of mainly concentrating on the “management of contact tracing, patient monitoring, and data gathering efforts,” Mandaue city was able to provide free COVID-19 testing and establish a department Local Task Force-Emergency Operations Center (EOC) specifically for the pandemic instead of the initial city health office. Mandaue city ended the year with a total of 2,549 coronavirus cases with 2,359 total recoveries and 172 deaths.

The first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic has strained and cost the lives of many. Both Local Government Units (LGUs) of both cities have become more attentive and responsive in comparison to the pandemic’s beginning in the Philippines. Cebu city has specified facilities depending on the severity of the patient's symptoms, strengthened a step-by-step approach to the containment of the virus, and most especially focused on mass testing in the barangays. Both cities have also decided to implement a focused department specifically for the virus called Local Task Force-Emergency Operations Center (EOC). As year 2020 comes to an end, COVID-19 mutates into a new strain that leaves Cebu city, Mandaue city, the Philippines, and the rest of the world to brace for another wave of a stronger coronavirus (Figure 2).

Figure 2: The table above plots the progression of additional monthly COVID-19 cases in Mandaue city (Bantay Mandaue, 2021) from March to December. The data was calculated with reference to the total number of cases found from the said source.

Budget analysis

Cebu city: Meanwhile, according to, the Cebu city vice Mayor required an ordinance of a “need-based” appropriation: “Must be directed at the pandemic; must address the flood problems; must deal with social concerns and food production; and must wipe out the city’s loan on the South road properties”. Certain amounts were cut away from the original included appropriations as they were not necessary for the year to follow. These lopped off or scrapped amounts included the budget for the traffic system’s artificial intelligence, economic recovery program, renovation of the legislative building, garbage collection under the department of public services, and the purchase of new vehicles for three offices. Cebu city had a P10 billion budget for 2021. An amount P400 million lower compared to the 2020 budget. The council had denounced some of the expenditures that were found to be unnecessary and not urgent and hiked up the budget for the acquisition of anti-flu and anti-pneumonia vaccines and medicines. The top priorities of the city government, as reflected in the budget appropriations are: Senior citizen financial assistance program, aid to the barangays and for the department of social welfare and services, in descending order. For 2020, the city was able to pass four supplemental budgets: Cash incentives for city Hall employees in honor of the celebration for the Cebu city charter day, purchasing of the PPEs, supplementation of the city’s expenditures in combatting COVID-19, and the hazard pay and cash invectives for some government workers.

Mandaue city: Departments conducting frontliner duties ought to obtain a large portion of the allocations or a bigger allocation in the 2021 budget of the city government. Their mayor, Jonas Cortes, emphasized the importance of focusing on other health issues on top of the government’s responses to COVID-19. This strategy will be applied to avoid the accumulation of varied health problems during the pandemic. Offices like the City Treasurer’s Office have had their allocations decreased, and expenditures on travel, training, and purchase of vehicles were supposedly suspended. Upon the submission of Mandaue’s 2021 budget, none of the expenditures for basic services of all departments and offices were compromised. As foreseen by Mandaue city treasurer, lawyer Regal Oliva, appropriations for cultural activities and trainings were cut.

In addition, Mandaue city will be focusing on the improvement of their capabilities on a more responsive information technology to adjust to the new normal. However, with the lack of information available on this, it isn’t possible to conclude the scope of their plans of expansion for the transitioning into the practices of the new normal. The Disaster Risk Reduction Management (DRRM) Fund, along with the COVID-19 response expenditures, had a P130 million allocations in the budget of which will be of a smaller amount in the following year. There was a P2 million increase in the budget allocation for Mandaue city hospital, amounting to P43 million, while Mandaue city Public market had P75 million. Despite the mention of priority to the public health sector of the government for the budget, the central hospital of the city still had a relatively smaller allocation than the city’s public market.

Implementation and regulation of COVID-19 protocols

National guidelines: In mitigating COVID-19, the department of health released the administrative order no. 2020-0015 through the office of the secretary of which presented the “Guidelines on the risk-based public health standards for COVID-19 mitigation”. Without an existing cure for the virus, these guidelines were to be followed to slow the spread of COVID-19. This document had the objective to serve as a guide for sectoral planning in mitigating the threat of the virus, and a basis in the process of decisionmaking and establishment of policies in response to COVID-19. Minimum public health standards of the DOH ought to be in place. The development of sector-specific and localized guidelines were to be centralized on these standards, no matter the setting. Three principles guide in adopting and implementing the standards: Shared accountability, evidence-based decision-making, and socioeconomic equity and rights-based approach.

Any new policy, investment, and action for the purpose of mitigating the virus should be guided by the following strategies, as presented in the document.

Increase physical and mental resilience:

•Ensure access to basic needs of individuals, including food, water, shelter and sanitation.

• Support adequate nutrition and diets based on risk.

•Encourage appropriate physical activity for those with access to open spaces as long as physical distancing is practiced.

•Discourage smoking and drinking of alcoholic beverages.

•Protect the mental health and general welfare of individuals.

•Promote basic respiratory hygiene and cough etiquette.

• Protect essential workforce through provision of food, PPE and other commodities, lodging, and shuttle services as necessary.

• Provide financial and healthcare support for workforce who contracted COVID-19 through transmission at work.

• Limit exposure of MARP groups, such as through limitation in entry or prioritization in service or provision of support.

• Provide appropriate social safety net support to vulnerable groups for the duration of the COVID-19 health event.

Reduce transmission:

•Encourage frequent hand washing with soap and water and discourage the touching of the eyes, nose and mouth, such as through appropriate information and education campaigns.

• Encourage symptomatic individuals to stay at home unless there is a pressing need to go to a health facility for medical consultation, if virtual consultation is not possible.

•Ensure access to basic hygiene facilities such as toilets, hand washing areas, water, soap, alcohol/sanitizer.

• Clean and disinfect the environment regularly, every two hours for high touch areas such as toilets, door knobs, switches, and at least once every day for workstations and other surfaces.

• Ensure rational use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPEs) that is suitable to the setting, and the intended user. Medical-grade protective apparel shall be reserved for health care workers and other frontliners and symptomatic individuals at all times.

Reduce contact:

• Implement strict physical distancing at all times, especially at public areas, workstations, eating areas, queues, and other high traffic areas.

•Reduce movement within and across areas and settings. Restrict unnecessary mass gatherings.

• Limit non-essential travel and activities.

• Install architectural or engineering interventions, as may be deemed appropriate.

• Implement temporary closure or suspension of service in high risk areas or establishments, as necessary.

Reduce duration of infection:

• Identify symptomatic individuals and immediately isolate, such as through the use of temperature scanning, symptom self-monitoring, and voluntary disclosure.

• Coordinate symptomatic individuals through appropriate health system entry points such as primary care facilities or teleconsulting platforms.

• Trace and quarantine close contacts of confirmed individuals consistent with department of health guidelines.

For the implementation of the guidelines, risk severity grading (low, moderate and high severity), risk-based public health standards across settings and prioritizing additional mitigation strategies based on modification potential should be considered. In the face of this pandemic, LGUs ought to: Ascertain the implementation of risk-based public health standards for COVID-19 mitigation; establish procedures in monitoring the compliance and submission of reports based upon the provided tools; coordinate with the necessary government agencies in the implementation of these guidelines; inaugurate counterpart l ocal ordinances, to ascertain compliance of their constituents; and ascertain that none of their constituents is deliberately cut off from being aware of these guidelines. On the other hand, industries and the private sector ought to pay heed and follow through the public health standards established by DOH, sectorspecific policies and plans by other national government agencies and other significant rules and regulations in the mitigation of COVID-19.

Cebu city

Guidelines: Cebu had been following the guidelines based on the executive order no. 064’s. 2020, an order enforcing enhanced community quarantine. This EO entailed a strict home quarantine, suspended public transportation, regulated food and health services, and ban of arriving international flights. Strict implementation of these guidelines were ensured by uniformed personnel, specifically involving the help of AFP and PNP. With the mandatory stay at home order, everyone in the city of Cebu were expected to stay at home and movement extending outside the borders of their household was only allowed for access to basic necessities. In addition, only one member of the household may fulfill this purpose. This specific order did not apply to a portion of the population; some of them included the health professionals, emergency personnel, authorized government workers and the like.

The EO is inclusive of the rule where in government work shall not be disrupted as long as they continue to operate with newly adopted alternative arrangements for their work in line with the civil service commission memorandum circular no. 07’s. 2020. However, although there was a non-disruption of government work, there was a temporary closure of businesses except for some necessary facilities like: Hospitals, pharmacies, gasoline stations, etc. Some of the running establishments during the ECQ, like food establishments, food manufacturers and laundry services, had to operate within limited operating hours, specifically only until 8:00 PM in the evening. To ensure the compliance of the different sectors of the industry, enforcement of compliance for businesses was also entailed in the EO. This highlighted that failure to implement the full extent of the guidelines would lead to having their respective establishments Business Permit revoked with the filing of the appropriate legala ction. Therew as a suspension of all operations of land vehicles and restriction of land and sea travel.

On top of this, border control was done by strict monitoring of the borders of the city where only specific individuals could enter or exit the city. There existed border checkpoint and operations as well to further establish this border control. Every border exit and entry in Cebu city was installed and operated twenty-four hours a day. The EO specified the strict prohibition of sharing of unverified information, such as submission of unconfirmed and invalid reports. These will have appropriate legal actions and those who commit this mistake were immediately considered as violators.

The last part of the guidelines for the pandemic included the necessary participation of the barangay. Each barangay and their corresponding officials and other force multiplies were expected to actively involve themselves in the implementation of the EO. In fact, non-compliant barangay officials would be facing consequences provided under the relevant laws and issuances appropriate to them.

Implementation of protocols: Upon the declaration of the guidelines by the Mandaue City Government, transportation was suspended; there was a regulation in supplying food and essential services, and an increase in presence of uniformed personnel to administer the qsuarantine operations. The government of Mandaue city didn’t implement more firm border control as they focused on intensifying their efforts on implementing the health protocols of their barangays. This was requested by the Mandaue city Mayor Jonas Cortes in the hopes of battling the spread of the virus within Mandaue city.

As an act of submission to the declared order of 4the government, all residents were ordered to comply with the given guidelines and policies implemented by the Mandaue city government. The PNP, with the assistance from business completely implement the order. Those mandated to execute the order in their corresponding jurisdictions were the barangay captains, officials, tanods and other force multipliers, with the aid of law enforcement agencies. Moreover, establishments allowed to run during the pandemic ought to have their respective managements assign a firm skeletal workforce in implementing social distancing protocols and the provision of sufficient transportation for their respective employees.

Mandaue city

Guidelines: In the city of Mandaue, the newly stapled guidelines were based on the executive order no. 83’s. 2020. The document’s scope includes the specifics on the curfews, liquor ban, public exercise, class and public transportation limitations, the mandatory stay-at-home, allowed movement and travel, allowed business under MGCQ, general business operations guidelines and their allowed capacities, prohibited establishments and operations, and minimum public health standards. These minimum public health standards include the wearing of face masks in public places and face shields in the workplace and public transportation, hand washing and proper personal hygiene, physical distancing and regular disinfection. The 24-hour curfew was for the senior citizens and those below 21 years old and the 10:00 PM to 5:00 AM curfew was for the rest of the citizens. The curfew had six exceptions:

•When getting essential goods and services, education purposes.

• Must always bring their quarantine passes.

•An authorized person outside of residence.

• Working in BPOs and other industries allowed to operate beyond curfew hours.

• Health workers.

• Government agencies providing frontline and emergency services.

The guidelines of the liquor ban during the pandemic were uniform to the ban existing pre-pandemic. On the other hand, public exercise was now limited to indoor and outdoor non-contact sports provided that the minimum public health guidelines were observed. Additionally, public transportation shall be limited to those provided or allowed by the LGU, public conveniences permitted by LTFRB, tricycle-for-hire with a Special Permit to Operate issued by the City, and taxis and TNVS. Although, there were prerequisites to be satisfied upon accessing these transportations:

• Strict one (1) meter distance between passengers shall be observed, given that all passengers are wearing face shields and face masks during the whole duration of their trip.

• Observance of minimum health standards.

Upon the onset of the pandemic there was also a mandatory stay-athome guidelines to be followed for any person below 21 years old and above 60 years old, with immunodeficiency, comorbidities or other health risks, pregnant women, and any person who resides with these mentioned groups of individuals. The exceptions included: When obtaining essential goods and services and with quarantine passes, or for work in permitted industries and offices, or those who are Authorized Persons Outside Residence (APOR). Apart from the mandatory stay-at-home, movement and travel was only limited to accessing essential goods and services, for work in the offices or industries permitted to operate and other permitted activities.

There are also existing guidelines for businesses under MGCQ. Specifically, all permitted establishments under categories I, II, and II as classified by DTI are allowed to operate or to be undertaken at a full operational capacity. The general business operations guidelines are as follows: All business establishments and the general public were advised to follow the minimum public health standards under executive order no. 77, IATF, Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) Issuances and the Department of Health (DOH) Issuances which shall form part of the business contingency health safety protocol. The allowed businesses were also expected to operate only at certain capacities. The prohibited establishments and operation included the holding of traditional cockfighting and operation of cockpits, beerhouses and similar establishments whose primary business was the service of alcoholic drinks, kid amusement industries like playrooms and rides, entertainment industries, concerts, and concert halls. In regards to schooling, there were only limited face-to face classes with distance learning as the main means of instruction. In-person classes were, in fact, only conducted in Higher Educational Institutions (HEIs), given that there was a strict compliance with minimum public health standards, consultation with local government units, and compliance with guidelines set by the commission on higher education. However, HEI activities involving the mass gathering of their constituents were still prohibited.

Implementation of protocols

There was a strict implementation of the guidelines in preventing further COVID-19 transmission, even as the local government already transitioned from ECQ to GCQ. Implementation of the minimum health standards was strictly called forth by the government and more binding penalties were implemented for violations against the protocols and guidelines. The city government had intensified enforcing the health guidelines, monitoring and apprehension of the violators in safeguarding themselves against the virus. Cebu city focused on areas of large active cases and isolated the positive cases to isolation facilities in order to enable the city to move from ECQ to a classification of a lower level. In addition, the city government had tightly monitored the running business establishments, while the police and military had consistently remained visible to secure the compliance of the city’s constituents to the protocols.

In implementing the order, imposed by the city government of Cebu, the COVID-19 Inter-Agency Task Force for the Management of Emerging Infectious Diseases (IATF) were particularly appointed to monitor the compliance of the barangays onto the health protocols. In evaluating the cause of the rise in the cases of COVID-19 in the city and developing a solution for this phenomenon, environment secretary Roy Cimatu was specifically appointed by President Rodrigo Duterte. He declared that many Cebuanos have already been obeying the protocols and regulations of the IATF and was even hoping to have no urgency in needing the uniformed personnel to be extremely forceful in implementing the regulations. In keeping up with the rising number of COVID-19 cases, Cebu had prepared 50,000 rt-PCR test kits, personal protective equipment, and sufficient nurses and hospitals, and three operational quarantine centers, which totals to a capacity of around 300. However, as discipline is a factor to be considered in combating the spread of the virus, health secretary Francisco Duque III appointed the LGUs to ensure discipline among their people. Due to the rising number of cases and the risk of furthering the lack of supplies and health capacities, enhanced community quarantine was implemented to buy the government some time to supply these.

Comparative analysis

Both of the cities did not move towards the direction of implementing stricter border controls in preventing another surge of COVID-19 cases. Instead, the cities focused on enforcing the minimum health standards especially upon the discovery of new cases. Parallel to the recommendations of DOH, both cities complied and indeed prioritized implementing the minimum health standards in fighting against contracting the virus. The presence of uniformed personnel was consistent in both cities. Both cities also had a delegation of responsibilities among their government agencies and respective officers, and key persons designated to do specific tasks for the benefit of the community. Moreover, the two cities also ensured the regulation of their necessities, and essential services. Although their many similarities, the two cities also had some differences in implementing the guidelines. For instance, Cebu had been selective on which areas to focus on as some of the areas had more active cases. Mandaue, on the other hand, had not considered being selective on their protocol enforcement.

Gap analysis

With what has been described about the current COVID-19 situation in the province of Cebu, more specifically for the cities of Cebu and Mandaue, this section aims to provide an analysis of the national and local governments’ responses.

These will be compared to the WHO standards, as well as the most recent DOH and IATF guidelines. This is guided by the goal of assessing the gap, while introducing the criticisms and commendations of both in dealing with the pandemic. Included here are the responses from the Cebu City Mayor, medical professionals and residents from Cebu and Mandaue, as local stakeholders in the pandemic. The interviews were conducted in order to further gain insight on the experiences and opinions of locals, with consideration of the WHO’s Six Building Blocks of Health Systems.

The WHO continues to produce health system concepts, synthesize and disseminate information, and build scenarios for the future. Part of these global norms are the systems and networks for identifying and responding to outbreaks. Thus, the WHO’s COVID-19 guidelines serve as the standard for health protocols around the world. On February 4, WHO International released the strategic preparedness and response plan, in response to the then-named 2019 novel Coronavirus (nCoV). Working closely and quickly with Chinese authorities and global experts, the plan outlined public health measures and international community standards to guide all countries to prepare and respond to the 2019-nCoV. Included in the document were the situation assessment, response strategies, and monitoring framework. Six strategic objectives were enumerated:

• Limit human to human transmission, including reducing secondary infections among close contacts and healthcare workers, preventing transmission amplification events, and preventing further international spread from China.

• Identify, isolate and care for patients early, including providing optimized care for infected patients.

• Identify and reduce transmission from the animal source. Address crucial unknowns regarding clinical severity, extent of transmission and infection, treatment options, and accelerate the development of diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccines.

• Communicate critical risk and event information to all communities, and counter misinformation.

• Minimize social and economic impact through multisectoral partnerships.

Three main methods to achieving these objectives were outlined. Firstly, the rapid establishment of international coordination would be necessary to develop support through existing mechanisms and partnerships. Second, country preparedness and response operations are to be scaled up, including rapidly identifying, diagnosing, and treating cases. This includes tracing of contacts, when feasible, infection prevention in healthcare settings, and additional health measures in travel and communication and communication engagement to inform the population. Lastly, priority was placed on innovation and research in order to accelerate the spread of transparent information regarding equitable availability of candidate therapeutics, vaccines and diagnostics. From this, further guidelines were produced regarding more specific aspects of the pandemic. After the first 100 days of COVID in the Philippines, the WHO shared a summary of their key actions in support of the country’s response. This included contact tracing, infection prevention, therapeutics access, clinical care, mental health intervention, community engagement and logistical protocols among other important systems. The WHO’s recommended the following requirements in the future public health and social adjustments in the context of COVID-19 for the Philippines: COVID-19 transmission is controlled through two complementary approaches:

• Breaking chains of transmission by detecting, isolating, testing, and treating cases.

• Quarantining contact and monitoring hot spots of disease circulation.

• Sufficient public health workforce and health system capacities are in place.

• Outbreak risks in high-vulnerability setting are minimized. Preventive measures are established in workplaces.

• Capacity to manage the risk of exporting and importing cases from communities with high risks of transmission.

• Communities are fully engaged.

A Monitoring and evaluation framework, updated in June 2020, was released in order to assess the performance and establish a set of globally acceptable indicators for support. The Framework was organized around a geographical scope, planning and monitoring needs, and the nine indicators (pillars) of each country as dimensions of their response. The Six Building Blocks of the Health System provide an organized means to monitor the inputs and results of policies, assess overall health system performance and evaluate the need for reform.

Health services

Health services refer to those which deliver personal and non-personal health interventions, reflecting the most immediate outputs of the health system, such as the distribution of necessary care, with minimum waste of resources. This includes healthcare facilities and centers. At the national level, the implementation of lockdown protocols and contact tracing measures began quite late. Moreover, public cries for mass testing were initially rejected by the DOH. This slow movement of the Philippine government reflected on its constituents, such as the ones residing in the province of Cebu.

With respect to equipment, many hospitals struggled to quickly procure testing kits, protective gear, and laboratory results. Many doctors were made to purchase their own equipment, as the hospitals’ limited supplies were instead allocated to nurses and orderlies who might not be able to afford them. The WHO released considerations in June 2020 regarding guidelines on how to save, assign and properly reuse PPE in certain circumstances. Based on this, some hospitals were able to stretch their supplies slightly. Vicente Sotto memorial hospital’s RT-PCR lab had only opened on March 20. Before that, all swabs needed to be sent to RITM in Metro Manila, causing massive backlogs. Some patients had even died while waiting for results. Developments in medical technology were also made over the course of the year. PAPR systems, intubation boxes and more affordable PPE were eventually more accessible to Cebuano hospitals.

According to the interviewed residents who availed of medical services within the last 10 months, they perceived the hospitals to be stricter in their restrictions. As a result, some services were slow. However, some commend the efforts of some institutions to make their services more accessible. These include drive-through rapid testing, online booking for appointments and the creation of clear guides for patient protocols. Though, some health centers were reported to have cramped waiting rooms, which violate physical distancing guidelines. Majority of hospitals were able to follow proper isolation procedures, and general testing and protection guidelines. However, the largest points of concern come from the lack of health system capacities within provincial health institutions. Though statements were released by high-profile locals that the hospitals could accept more patients, most healthcare workers said otherwise. In reality, at some point, hospitals began turning away certain patients. This could imply that the gap within the health service is heavily related to the available resources and the access to the necessary resources in order to appropriately treat more patients. There also needed to be more efforts regarding the access to these services. As an issue that has existed long before the pandemic, the local government seems to have done little in fully protecting the spectrum of members in the community. Though, attempts have been made by some barangay-level government units to provide goods. Some financial aid has also been given at the national level through a Social Amelioration Program, but a provincial-scale government effort is yet to be seen.

Initiatives were also done by benevolent third-parties to help the affected, less fortunate members of the community without access to safe spaces to self-isolate. One such initiative was called the Bayanihan field center quarantine facilities set up by a private entity called Bayanihan Cebu PH. The centers were run by DOH field officers.

Health workforce

The health workforce refers to all professional and non-professional workers under the healthcare system. Human resources serve as one of the key input components of the health of system, and work towards responsive, fair and efficient provision of service. These are done to the extent which the resources and circumstances allow. It is imperative that all members of the health workforce are given the appropriate tools to be competent and productive, such as training, fair working hours and sufficient manpower. Health workers serve as some of the frontliners in this pandemic. Despite their important role in our current circumstance, some HCWs around the world were treated with hostility and violence from regular citizens. In Cebu, reports of nurse getting harassed on the streets and doctors getting shamed for voicing opinions made the news. In hospitals, personnel were all made to undergo training on the proper donning and doffing of PPEs for their protection. However, the plethora of protocols and the fear of the virus proved to be too much for some. In the beginning, the uncertainty, struggle and sudden loss of close interactions among co-workers only added to the difficulty of their daily grind. Most of all, the death of some of their colleagues and staff decreased the overall morale, expressed by one of the interviewed doctors. According to them, morale was improved as the protocols were streamlined, and became second nature around the premises. Some point out that morale wasn’t too deeply affected because, as doctors, they recognize what is necessary for the services they are called to provide. In September, the WHO released guidelines on the risk assessment and management of HCWs in the current context.

This specifically gives advice on dealing with HCWs who have been potentially exposed to the virus. Depending on their level of exposure and the presence of symptoms, hospital administrators are expected to clearly provide opportunities for their constituents to isolate and quarantine over a certain period before they can return to work. More than this, the WHO later released protocols for handling and disinfecting packages and parcels that carry cargo, as they are potential fomites. One highly salient point made by the WHO’s recommendation for the Philippines is to keep in mind that the workforce must remain sufficient, and are provided with appropriate allocations. Once the COVID-19 cases quickly started rising, doctors and nurses were threatening to resolve themselves from their position. This somehow explains how many hospitals experienced understaffing, especially in instances of potential department-wide contact. Frontliner Dr. Rene Josef Bullecer told Inquirer in an interview, “As a health-care professional, I urge able doctors to serve the city. In the medical profession, there is no such thing as retirement.” There are retired doctors and nurses whom he appealed to for help due to the surge of COVID-19 patients. The cry of Cebu city’s healthcare professionals, especially after the massive surge of ases, urged Filipino Nurses United, a nurses’ union, to call for mass hiring and health secretary Francisco T. Duque III to issue a directive to populate Cebu city with ‘Doctors to the Barrios’ (DTTB) and other healthcare professionals. DOH approved Duque’s request and had prepared for the deployment of the DTTB and other healthcare professionals.

Health information systems

The production, analysis, dissemination, use of reliable and timely information on health determinants, performance and status refer to a well-functioning health information system. This information serves as one of the bases for the overall policy and regulation of all other health system blocks WHO continues to share updated information on guidelines, as well as further efforts to disseminate information to the public easily via info graphics, video explainers, and more. Other sources also exist such as reliable news outlets and government databases. However, within the province of Cebu, it must be noted that transparency reporting on COVID-related efforts decreased and halted by the end of May. In this digital setting, it was only expected that misinformation and fake news made its way into the discussion of COVID-19. At most, social media discourse has become the main driver of the spread of information to the population. Separate from the problematic nature of these platforms, such as the lack of accountability, regulations and active preemptive measures, it has not helped that some high-ranking politicians have spread medical misinformation. Nationally and locally, some officials endorsed the use of steam inhalation, locally known as “tuob”, as a COVID-19 remedy and treatment.

In Cebu, some officials have made claims in passing regarding herbal alternatives, that are not backed by scientific evidence. This chain reaction from one spread of misinformation to another is contributory to the overall engagement of the citizens.

Another significant issue arises as DOH’s data drop for COVID-19 is not reflected in Cebu city’s and Mandaue city’s websites. This was observed by the researchers of this paper.

The deficiency and consistency of COVID-19 updates and information could be a contribution to the miscommunication of communities and should be a major priority for the sake of the country’s progress and the citizens’ awareness. Based on interviews, residents have found that LGUs have not been able to fully engage the community, more especially in educating them of the realities of this pandemic, as well as transparency on future efforts. This violates the WHO guideline on “communities are fully engaged.” As stated by Limpag with reference to the COVID-19 forecasts in the Philippines: Post-ECQ report by university of the Philippines researchers, cultivating a culture of open data sharing will go a long way to improving everyone’s effectiveness in contributing to the fight to stem the pandemic.

Service delivery

Service delivery, within the health system, is defined as the efficient delivery of health interventions, while ensuring equitable access to safe and quality medical products and technologies. This includes ascertaining the availability and use of cost-effective alternatives to these services. In the early months of the pandemic, Cebu faced numerous challenges. Only locking down in late March, the LGU response was seen as too little, too late. The lack of travel restrictions over months allowed for an influx of passengers from China. At this point, the IATF had only begun endorsing the use of masks in March. However, this was earlier than the WHO, which only recommended universal mask wearing by June. To add to the late action, Cebu still managed to host the Sinulog Festiva. Only after March 28’s lockdown did it seem that the local government began getting some traction in their efforts. The move to prepare public clinics, as well as begin cracking down on the outbreaks in congested, urban poor areas is what eventually led to a rising number of positive and presumed-positive cases. Hospitals were now forced to cope with this reality. With the need for additional precaution, equipment, and time at every stage of patient care, most were very quickly overwhelmed. Across different institutions, commonalities in newly developed protocols exist such as:

• Separation of COVID, non-COVID, COVID-suspect patients in ICUs, ERs, ORs, wards and elevators.

• Mandatory RT-PCR tests for all symptomatic patients with relevant history.

• Triage of patients prior to entrance into the hospital. Full PPE to be worn in all aerosolizing procedures.

• Minimum protection to Level 3 (non-COVID) in all surgical procedures.

• No elective surgeries to be performed.

• Airway protocols for anesthesiologists: Only by highly qualified doctors.

• Regulation of entrances and hallways (doctor and patient flow charts to dictate movement across the hospital premises), with frequent temperature testing and alcohol disinfection.

• Limit the number of visitors and significant others for all patients. Equipping of air filters, negative pressure rooms, and plastic barriers.

• Required wearing of masks together with standard physical distancing measures.

While all interviewed healthcare professionals agreed that these additional efforts were effective, some argue that the processes could have been more efficient. As a result of the new, long list of protocols, all hospital systems were slowed. Moreover, some hospitals had not been able to immediately and strictly implement the policies. All of these measures consequently aid in ensuring the lessening of transmission chains. These preventative measures, as followed by hospitals all help quell the spread of the virus.

Health financing

In order to ensure access to affordable healthcare, the health system requires a stable source of health financing. As another key input component, adequate funds are necessary to protect the system from financial catastrophe.

This includes donations, subsidies and even wages as incentives for efficiency. In both Mandaue and Cebu, LGUs have begun to make plans to increase budgets in favor of the COVID-19 response. Many of the financial budgets were allocated to the purchasing of medicines, the acquisition of more information technology, as well as the appropriations for the financial assistance of impoverished sectors. However, criticism has fallen on the LGUs due to the lack of transparency in the budget allocations of the time. Provincial reports were released showing that “tuob” kits were purchased worth P2.5 million. This was denounced by the public; thus, demonstrating inefficient health financing through the appropriation of the city’s budget onto wasteful expenditures, such as the ‘tuob’ kits. Some of the common reasons for inefficiency in health financing, based on the world health report, can be observed in the published information of budget appropriations during the pandemic. First, there’s nebulous resource allocation guidance and a lack of transparency on the budget of both cities. Ensuring transparency in purchasing is reportedly one way of addressing inefficiency in the health system. Even as of now, it is quite difficult to access transparency reports from government budget databases. In fact, both government sites of Mandaue city and Cebu city had no budget report for the year 2020 or the year 2021. None of the government agencies from both cities also provided for the aforementioned report. Second, the presence of inefficient procurement/distribution systems, as can be observed in the unnecessary purchasing of ‘tuob’ kits only based on incredible claims. The inability to have efficient procurement/distribution systems can have major consequences for the government and its constituents. Purchases misaligned to the needs of the community may cause a social uproar, and have major implications for the overall state of any city, especially during a pandemic. According to interviews conducted with local HCWs, in some situations, the hospitals became heavily reliant on private donations from third parties. This only proves the need for more action from the government.

Leadership and governance

Finally, at the core, Leadership and governance ensures the strategic implementation for policies and frameworks within the health system. Combined with effective oversight, coalitionbuilding, regulation, attention to system-design and accountability, this block should aim to protect, as well as appropriately regulate, the interactions of its constituent parts. In March 2020, Congress passed the Bayanihan to Heal as one act, which grants President Duterte special powers during this pandemic. This move was done in the hopes of expediting the actions of the national government in response to the pandemic. According to a statement issued by the OPS, this includes the “immediate implementation of measures for the effective education, detection, protection and treatment of our people versus COVID-19; expediting the accreditation of testing kits and facilitating the prompt testing by public and designated private institutions; providing allowance or compensation and shouldering medical expenses in favor of public and private health workers; directing establishments to house health workers, serve as quarantine areas or relief and aid distribution locations, as well as public transportation to ferry health, emergency and frontline personnel; ensuring the availability of essential goods, in particular food and medicine and protecting the people from illegal and pernicious practices affecting the supply, distribution and movement of certain essential items; directing the extension of statutory deadlines for the filing of government requirements and setting grace periods for payment of loans and rents and providing subsidy to low-income households and implementing an expanded and enhanced Pantawid Pamilya Program.

However, it is important to question why such extreme measures were necessary, especially in terms of the natural democratic processes that are involved amongst the aforementioned responsibilities. This is potentially linked to the lack of pandemic preparedness measures prior to the actual breach into our borders. For months, Chinese officials had been warning the world about the spread of the virus. Dr. Fauci of the US had also mentioned even 3 years prior as to the likelihood of a deadly outbreak within the Trump administration’s term. Thus, the world wasn’t ignorant; instead, it was merely caught off guard. After the height of COVID positivity in Cebu, IATF officials began to pit “discipline” as the main factor in solving the pandemic, especially in relation to the implementation of protocols in barangays. Though, as previously mentioned, the community engagement and education programs were limited, thus preventing any organic obedience to the said implementations. Criticism for public officials is not uncommon. However, during this pandemic, the national and local governments have faced a different level of scrutiny from the public. As the ultimate sources of transparency and accountability, it is imperative that they recognize the impact of their actions. Locally, criticism fell on numerous officials from experts for claiming that the state of hospitals and the community was actually better than the reality. More than this, evidence of VIP testing and treatment at the national level caused a stir. An analysis of the Philippine government’s response by the Guardian emphasizes how the government action was not as timely or effective as necessary. In line with interview responses from local residents, the government should have been more rigorous in the initial months of lockdown, ensuring that the spread of the virus was limited.

The lack of preparedness by the Philippines was evident in the first few months of 2020. However, the downfall of proper governance during those times were digested and comprehended for the recovery of the nation. Based on the interview with Cebu city Mayor, the local government has acknowledged their downfall when the COVID-19 epicenter” label was placed on the city. However, the city was able to bounce back by implementing and enhancing the necessary teams for effective regulation. Labella believes that “the best and most aggressive was the contact tracing team. The team is segregated into five different health areas in the city and has adopted the test, trace, treat, and isolate approach which follows a step-by-step procedure: Test walk-in patients, both symptomatic and asymptomatic, for free; contact trace and swab the patient’s close contacts, but this step is also extended to arriving passengers from airports and seaports; treat and isolate patients who are COVID-19 positive which have specific areas depending on the severity of the patient’s symptoms. Cebu city along with Mandaue city is continually striving to mitigate the transmission of COVID-19 in the area.

When the coronavirus landed and infected the citizens of the Philippines, lockdowns were placed, businesses were closed, and masks were obligatory. Cebu city and Mandaue city, as well as the Philippines and other countries, came unprepared in terms of teams, services, and facilities due to the suddenness of the virus. Both cities focused on COVID-19 testing and treatment throughout the year, however, the major spike in June for Cebu city and July in Mandaue city was due to the increased number of testing and most importantly, early easing of quarantine measures when COVID-19 cases were projected to be an upward slope. Lives were saved, but many lives were lost as well. However, when Cebu city became the epicenter of COVID-19 in the Philippines, they were able to bounce back by reverting back to ECQ from GCQ, increasing their police and military force, COVID-19 beds, and isolation centers, and authorizing the city’s Emergency Operations Center (EOC to design a better COVID-19 response. Similar to Cebu city, Mandaue city saw the necessity of contact tracing and a department focused on COVID-19 response and enhancement of testing, facilities, and treatment. Both cities veered from implementing stricter border controls to focus on the enforcement of minimum health standards and multiple portions of the budget of both cities were lopped off to leverage its resources for their throttle against the spread of COVID-19. Clearly, from the cities’ implementation of their respective guidelines and budget appropriation, public health is their priority. The disparity between Cebu’s LGU response to the COVID-19 pandemic and the national and international standards is currently one that is not too large.

As mentioned by Mayor Labella, the actions taken are meant to be connected to that of the WHO, DOH, and IATF. However, based on what was analyzed, the gap seems to stem from a generalized delay in action. This is mentioned to be found at all levels of governance, starting at the national level. This is affected by the slow dissemination of information, the spread of misinformation, and ultimately, the sentiment against more stringent measures. What can be commended, though, is how the collaboration between the LGUs and the residents of Cebu have only grown since the beginning of this pandemic. The calls for transparency, accountability, and aid from the people have proven to be effective in at least sparking a form of discourse. Through this, more efficient systems, policies and implementations continue to be put into motion. With the coming months, leading to talks of vaccination and the future of the province, it is essential that these interactions remain at the forefront.

Based on the COVID-19 response, overall efforts and performance of both cities, the writers recommend the following in moving forward with the New Year:

• Establishment of a database with sufficient information of published researches on ensuring the implementation of riskbased health standards for the mitigation of COVID-19.

• This is to counter the lack of accessibility, inconsistent data from DOH and the city websites, and outdated sections in the city website’s transparency sections.

• Activation of communication lines between the government, health centers, LGUs, and government agencies and the people.

• Addition and strengthening of programs on mental health and general welfare of individuals which are stated in the national guidelines of providing protection to these sectors.

• Budget appropriation for the development of a social safety net support to vulnerable groups. This would give importance and sufficient protection to those most vulnerable to the virus and the implications of the pandemic onto their livelihood.

• Continued strict and proper enforcement of physical distancing and health safeguards as restrictions are implemented in preparation for the mutated strain. As the world enters another year with the coronavirus, it is valuable to remember that these listed recommendations are aimed at improving the regular systems within the society. Should a “new normal” be achieved, these could strengthen community engagement and overall efficiency within the LGUs.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Citation: Felisse GL, Inaki RJ, Nicole RC. " Philippines and Regional/Provincial Responses and Approaches to Addressing the COVID-19 Pandemic". Health Econ Outcome Res, 2023, 9(2), 001-009.

Received: 02-Aug-2021, Manuscript No. HEOR-23-24341; Editor assigned: 05-Aug-2021, Pre QC No. HEOR-23-24341; Reviewed: 19-Aug-2021, QC No. HEOR-23-24341; Revised: 08-May-2023, Manuscript No. HEOR-23-24341; Published: 08-Jun-2023, DOI: 10.37421/2471-268X.23.9.2.001

Copyright: © 2023 Felisse GL, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.