Research Article - (2023) Volume 13, Issue 8

Background: Worldwide anemia is a common health problem, especially in developing country like Ethiopia, the prevalence of anemia among adolescent girls is a mild to a moderate public health problem. As well as, nutritional knowledge and diversified food consumptions is low. Besides, there is a few studies done on anemia among high school adolescents in Ethiopia, and no documented studied is found in the study area.

Objectives: The aim of this study is to assess the magnitude of anemia and its associated factors among high school adolescent girls in Mizan- Aman Town, Bench Sheko Zone, Southwest Ethiopia.

Methods: Institutional based cross-sectional study design was conducted in Mizan-Aman Town from March 01 to 30, 2022.data were entered in to Statically Package Social Science and on bivariate analysis p≤0.25were candidates for multivariable logistic regression.

Results: The prevalence of anemia was 23.5% with (95%CI: 18.9, 28.8). Father education(AOR=1.27;95%CI:0.67,5.70;P=0.0014),family size(AOR=3. 23;95% CI:1.13,5.78;p= 0.0),wealth index(AOR=6.00;95%CI:2.31,15.7;p=<0. 001),duration of menstruation (AOR= 2.63;95% CI1.03,6.67;p=0.043) and dietary diversity score (AOR=2.13;95%CI:1.16,8.43;p= 0.024) were determi nant factors.

Conclusion: Prevalence of anemia among adolescent girls was a moderate public health problem. Therefore, attention should be given on iron-rich food, nutritional education, and diversified food consumptions to reducing the burden of anemia.

• Quality of life • Severe mental illness• WHO QoL-BREF• Gondar • Ethiopia

Anemia is a condition characterized by a reduction in the number of red blood Severe Mental Illness (SMI) is defined as a mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder resulting in serious functional impairment. Schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder with psychotic features are considered SMI. They substantially interfere with or limit one or more major life activities [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that SMI affects 4% of the adult population worldwide [2] and 4.2% U. S adults and is higher among women (5.3%) than men (3.0%) [1].

According to the WHO (2011), untreated mental disorders exact a high toll, accounting for 13% of the total global burden of disease. Major depressive disorder is the 3rd leading cause of disease burden, which accounts for 4.3% of the global burden of disease, and the estimate for low- and middleincome countries were 3.2% and 5.1% respectively. Depression will be the leading cause of disease burden globally by the end of 2030, according to WHO. Mental illness accounts for 25.3% and 33.5% of all years lived with a disability when only the disability component is taken into account in the calculation of the burden of disease in low- and middle-income countries respectively [3].

WHO (1998) defines the Quality Of Life (QoL) as “individuals' perceptions of their position in life within the context of the culture and value systems during which they live and about their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns”. The quality of life, based on this definition refers to a subjective evaluation that is embedded in a cultural, social, and environmental context. Because this definition of quality of life focuses upon respondents' perceived quality of life. So, it is not expected to provide how of measuring any detailed symptoms, diseases, or conditions, but rather the results of disease and health interventions on quality of life [4]. The scope of quality of life, in general, extends beyond traditional symptom reductions and includes patients’ subjective feelings of well-being, satisfaction, functioning, and impairment [5]. Currently, QoL is counted as an important indicator of the impact of diseases on people who suffer from severe mental illness [6].

People with severe mental illness often lead an isolated and marginalized life in poor housing with a low income, little education, and poor vocational and social skills. Patients with severe mental illness are also prone to stigma leading to discrimination and thus affecting their quality of life [6-9].

Increased interest from patients with SMI and their relatives was focused not only on the improvement of symptoms but also on functioning and quality of life [7]. This implies a holistic treatment approach that considers the improvement in functioning and quality of life of patients with severe mental illness is crucial [8, 9]. However, professionals have increased focus on pharmacological treatments for symptomatic improvement by neglecting the client's other social, psychological, and environmental conditions [10, 11].Despite these diverse and complicated outcomes, the quality of life of people with severe mental illness is not well addressed in developing countries, particularly in Ethiopia except for a few studies done in Addis Ababa and Jimma [11] which assessed the quality of life among patients with severe mental illness and some associated factors. Therefore, this study assessed the quality of life and its associated factors which the previous study did not cover; like sleep quality and a group of patients who have a follow-up at the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital which was not part of the prior studies. The study played a significant role in the advancement of knowledge on quality of life and its associated factors, which in turn helped clinicians to consider the quality of life of patients with severe mental illness in attempts to treat the patients to not only reduce symptoms of illness but also to improve the quality of life of the patients.

General objective

To assess the quality of life and associated factors among patients with severe mental illness at the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Gondar, Ethiopia, 2021.

Specific objectives

To determine the quality of life among patients with severe mental illness at the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Gondar, Ethiopia, 2021. To identify factors associated with quality of life among patients with severe mental illness at the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Gondar, Ethiopia, 2021.

Study design and period

A cross-sectional study was conducted from May 1/2021 to May 30/2021.

Study setting

University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital provides tertiary care to the population of Gondar and its neighboring states, and most of its patients come from lower socio-economic strata. The hospital contains more than 400 beds and provides services in various departments and units including pediatrics, psychiatry, surgery, gynecology, dentistry, ophthalmology, pharmacy, medical laboratory, fistula, and others. The psychiatry clinic particularly contains 21 beds for admission and 4 outpatient rooms where 2 of them have one clerking table on each and the remaining two rooms, have two clerking tables each, at which two clinicians could see patients at once. On a monthly average, a total of 1200-1300 patients visit the outpatient units. Out of these, patients with severe mental illness whose age is greater than 18 years account for nearly 1000[12].

Study population: All patients with severe mental illness at the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital were available during the data collection period. In other words, all patients with severe mental illness were selected.

Inclusion criteria: Patients with severe mental illness who already started medication 6 months back on follow-up at out-patient units.

Exclusion criteria: Those who are unable to communicate (determined by clinical presentation or mental status examination)

Those who are acutely sick (determined by clinical presentation or mental status examination)

Sample size and sampling technique

Sample size: According to a one-year report from the university hospital’s psychiatric unit, nearly 15000 visit out-patient units. On average, 1200 patients visit out-patient units in a month. Out of this, around 1000 patients have a diagnosis of severe mental illness. To calculate sample size, a simple population proportion formula was employed to get the representative sample for the study.

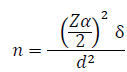

Where, ð?? = minimum sample size

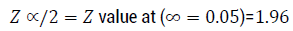

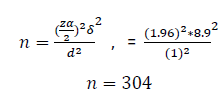

ð?¹2 = standard deviation of the mean quality of life score, SD from a previously published study in Addis Ababa in the social domain was 8.9 [13]

D = Margin of error (1)

Then, adding 10% (304 x 0.10 = 34) of the non-response rate, the total sample size for this study would be 304+30=334.

Sampling technique

To get a representative sample and to assure the selection possibility of eligible participants for this study, a systematic random sampling technique was used to get a total of 334 participants with severe mental illness from an outpatient unit of the clinic. Study subjects were identified based on information obtained from the client card. The total sample size was met by the systematic random sampling technique for a one-month caseload, (i.e., Kth value; K=N/n, 1000/334=2.99≈3). The selection skip interval was for every 3rd patient with SMI. The first study participants were selected out of three participants by the lottery method. Information was collected from every 3rd patient with severe mental illness entering 6 out-patient units/rooms.

Method of data collection/instruments and procedures

Demographic data were collected using a semi-structured questionnaire. Data on quality of life was collected using a standard questionnaire via interviews. The World Health Organization Quality of Life – Brief (WHOQOLBRFE), is a cross-culturally validated tool used to assess psychiatric patients’ quality of life. The WHOQOL-BREF includes 26 items measuring physical, psychological, social relationships, and environmental health domains. It has also two further items to evaluate the individual’s overall perception of quality of life and the individual’s overall perception of their health. In addition to its excellent validity and reliability, what makes WHOQOL- BREF different from other measurement tools of quality of life is, that it contains social and environmental aspects. Domain scores are scaled in a positive direction (i.e., higher scores correspond to a better quality of life) [13]. QoL raw scores are transformed into a range between 0 and 100. A score closer to a hundred indicates a good quality of life. The questionnaire was pretested at Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital among 5% of the respondents to check its consistency. Thus, Cronbach’s Alpha score was found 0.94.

Validated tools were used to collect data for the independent variables. Oslo Social Support Scale (OSS) for measuring social support was used; the score from 3-8 was considered to have poor social support; 9-11 scores were considered to be moderate and 12-14 were considered to have good social support, respectively. Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS – 4)was used to measure medication non-adherence and it is a self-reporting scale with 4 items scoring from 0 – 4. Patients who score 0 were considered high adherent; a score of 1-2 indicated medium, and a score of 3-4 was considered low adherent. The Jacoby Stigma Scale measures selfstigma with a scoring of 1 and above indicating the patient was stigmatized and 0 indicated not stigmatized. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) was used to measure the sleep quality of participants. A score of ≥5 was considered good sleepers and a score of <5 was considered poor sleepers based on PSQI. Items from ASSIST were taken to collect data about substance use [14].

Socio-democratic characteristics of respondents

More than half of the participants were predominantly male, 56% (n=180) with the mean standard deviation age of respondents was 36 (SD ± 11) years, and the majority of respondents were urban residents 59.4% (n=190). The majority of participants were married 42.2% (n=135) and only a small percent of participants were widowed 5.6% (n=18) Table 1.

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants.

| Variables | Categories | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (M±SD) | 36±11 | ||

| Sex | Female | 140 | 43.8 |

| Male | 180 | 56.2 | |

| Marital status | Single | 130 | 40.6 |

| Married | 135 | 42.2 | |

| Divorced | 37 | 11.6 | |

| Widowed | 18 | 5.6 | |

| Religion | Orthodox | 186 | 58.1 |

| Muslim | 96 | 30 | |

| Protestant | 16 | 5 | |

| Catholic | 16 | 5 | |

| Jewish | 6 | 1.9 | |

| Residence | Rural | 130 | 40.6 |

| Urban | 190 | 59.4 | |

| Educational status | Illiterate | 92 | 28.8 |

| Primary school | 81 | 25.3 | |

| Secondary school | 90 | 28.1 | |

| College degree and above | 57 | 17.8 | |

| Occupation | Student | 37 | 11.6 |

| Farmer | 109 | 34.1 | |

| Government employee | 41 | 12.8 | |

| Private employee | 47 | 14.7 | |

| No job | 86 | 26.9 | |

| Living arrangement | with family | 256 | 80 |

| Alone | 51 | 15.9 | |

| With relatives | 13 | 4.1 |

Clinical characteristics of respondents

Most respondents 53.4% (n=171) were patients with schizophrenia and the least 20.3% (n=65) were patients with the diagnosis of bipolar disorder. The majority of participants, 48.1% (n=154) have been treated for 2-5 years followed by 32.8% (n=105) and 19.1% (n=61) who have been treated for greater than five years and less than one year respectively. Concerning sleep quality, the majority, 92.5% (n=296) had poor sleep quality. More than half, 59.7% (n=191) were moderate adherents to the medication they were taking, and 21.3% (n=68), 19.1% (n=61) were low adherents and high adherents respectively (Table 2).

Table 2. Clinical characteristics of respondents.

| Variables | Categories | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of onset (M±SD) | 30±12 | ||

| Clinical diagnosis | Bipolar d/r | 65 | 20.3 |

| Major depressive d/r with psychotic feature | 84 | 26.3 | |

| Schizophrenia | 171 | 53.4 | |

| Frequency of episode | None | 49 | 15.3 |

| Continuous | 78 | 24.4 | |

| Two | 136 | 42.5 | |

| More than two | 57 | 14.8 | |

| Duration of treatment | <1 | 61 | 19.1 |

| 02-May | 154 | 48.1 | |

| >5 | 105 | 32.8 | |

| Diagnosed comorbid illness | Yes | 48 | 15 |

| No | 272 | 85 | |

| Medication non-adherence | High adherence | 61 | 19 |

| Medium adherence | 191 | 59.7 | |

| Low adherence | 68 | 21.3 | |

| Sleep quality | Good | 296 | 92.5 |

| Poor | 24 | 7.5 |

Psychosocial characteristics of respondents

Age, sex, marital status, religion, residence, educational status, occupation, diagnosis, frequency of episode, comorbidity, duration of illness, duration of treatment, living arrangement, medication adherence, social support. More than half of the participants, 53.8% (n=172) were stigmatized. Participants who had poor social support accounted for 34.7% (n=111) followed by 34.1% (n=109) participants with moderate social support and the remaining 31.3% (n=100) had good social support Table 3.

Table 3. Psychosocial characteristics of respondents.

| Variables | Categories | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stigma | Not stigmatized | 172 | 53.8 |

| Stigmatized | 148 | 46.3 | |

| Social support | Poor support | 109 | 34.1 |

| Moderate support | 111 | 34.7 | |

| Good support | 100 | 31.3 |

Substance use

The majority of participants, 62.5% (n=200) used one or more psychoactive substances in their life time. From a total of 320 participants, 8.1% (n=26), 50.6% (n=162), 22.5% (n=72), 3.8% (n=12) used tobacco products, alcoholic beverages, khat, and substances like cannabis, marijuana, pot, e.t.c.in their life time respectively. Participants who used one or more psychoactive substances in the past 3 months contributed 24.7% (n=79). From a total of 320 participants, 4.4% (n=14), 17.2% (n=55), 11.9% (n=38), and 2.2% (n=7) were used tobacco products, alcoholic beverages, khat, and substances like cannabis, marijuana, pot in the past 3 months respectively.

Quality of life among patients with severe mental illness

The total mean ( ± SD) score for overall quality of life was 49.16 (±15.64). The mean score for the physical, psychological, social, and environmental health domains were 47.96 (± 17.81), 54.12 (± 14.40), 45.79 (± 19.37), and 47.79 (± 16.83) respectively (see Table 4).

Table 4. Quality of life among patients with severe mental illness

| Variables | Range of possible mean score | Mean (±SD) | Minimum | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total quality of life | 0-100 | 49.16 (±15.64) | 9.25 | 79.75 | |

| 17.74 (±3.72) | 8.5 | 24.25 | |||

| Domains of quality of life | Physical | 0-100 | 47.96 (±17.81) | 13 | 81 |

| Jul-35 | 20.45 (±5.02) | 10 | 30 | ||

| Psychological | 0-100 | 54.12 (±14.40) | 6 | 81 | |

| Jun-30 | 19.00 (±3.44) | 8 | 26 | ||

| Social | 0-100 | 45.79 (±19.37) | 6 | 100 | |

| Mar-15 | 8.74 (±2.32) | 4 | 15 | ||

| Environmental | 0-20 | 48.77 (±16.83) | 0 | 81 | |

| Aug-40 | 23.07 (±5.36) | 8 | 34 | ||

| Items | Item 1 | 01-May | 2.88 | 1 | 5 |

Factors associated with quality of life among patients with severe mental illness

Use of the substance, stigma, and sleep quality were statistically significant on a simple linear regression model (Table 5).

Table 5. Simple linear regression model on quality of life among patient with severe mental illness.

| Variables | R2 | β | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.029 | -0.17 | -.380 - (.084) | .002 |

| Sex | 0.01 | 0.098 | -.365 - (6.547) | .079 |

| Marital status | 0.022 | -0.147 | -4.738 - (-.708) | .008 |

| Religion | 0.006 | 0.075 | -.582 - 3.125 | .178 |

| Residence | 0.11 | 0.107 | -.093 - 6.883 | .056 |

| Occupation | 0.01 | -0.101 | -2.417 | 0.073 |

| Living arrangement | 0.034 | -0.184 | -8.891 - (-2.298) | .001 |

| Educational status | 0.054 | 0.233 | 1.817 - 4.931 | 0 |

| Diagnosis | 0.044 | 0.209 | 1.991 - 6.244 | 0 |

| Frequency of episode | 0.032 | -0.18 | -4.763 - (1.182) | .001 |

| Comorbidity | 0.082 | 0.286 | 7.900 - 17.146 | 0 |

| Duration of illness | 0.097 | -0.312 | -9.045 - (-4.494) | .000 |

| Duration of treatment | 0.1 | -0.316 | -9.287 - (-4.662) | .000 |

| Medication adherence | 0.171 | -0.413 | -12.644-(-7.699) | 0 |

| Social support | 0.55 | 0.728 | 12.905 - 15.768 | 0 |

| Ever use of substance | 0.081 | 0.284 | 5.765 - 12.589 | 0 |

| Current use of substance | 0.069 | 0.263 | 5.678 - 13.387 | 0 |

| Stigma | 0.277 | -0.526 | -19.415-(-13.538) | 0 |

| Sleep quality | 0.05 | 0.224 | 6.921 - 19.670 | 0 |

Those variables with a p-value <.25 on a simple linear regression model were entered into a multiple linear regression model. Thus, Living alone decreases the mean quality of life by 5.867 when compared to patients who live with their families, and living with relatives increases the mean quality of life by 1.469 when compared to those patients who live with their families.Patients who had moderate social support increased the mean quality of life by 10.554 when compared to those who had poor social support and patients who had good social support increased the mean quality of life by 19.203 when compared to patients who had poor social support. Moderate adherent to their regimen/s (medication/s) had decreased mean quality of life by 1.662 units when compared to high adherents and those who were low adherent to their medication/s decreased the mean quality of life score by 6.579 units when compared to high adherent individuals when other variables were kept constant (Table 6).

Table 6. Multiple linear regression model for patients with severe mental illness.

| Variable |

Coefficient B | p-value at 95% CI | 95% CI for β | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Living arrangement |

with families | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| alone | -5.867 | 0.001 | -9.186 - (-2.547) | |

| with relatives | 1.469 | 0.607 | -4.093 - 4.154 | |

Social support |

poor | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| moderate | 10.554 | 0 | 7.423 - 13.686 | |

| good | 19.203 | 0 | 15.423 - 22.983 | |

Medication non-adherence |

high adherence | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| medium adherence | -1.662 | 0.269 | -4.614 - 1.289 | |

| low adherence | -6.579 | 0.001 | -10.494 - (-2.663) |

Quality of life was predicted by living arrangement, social support, and medication non-adherence contributed 64.18% of the variation (R2=0.6418, Adjusted R2 =.6314, F (9,310) =61.72, P<0.05).

The total mean score for the quality of life score was 49.16 (±15.64)[14]. The domains of quality of life mean scores were 47.96 (±17.81), 54.12 (±14.40), 45.79 (±19.37), and 47.79 (±16.83) in the physical, psychological, social relationship, and environmental health domains respectively. Study variables such as living arrangement, social support, and medication nonadherence were the main predictors of QoL among patients with severe mental illness [15].

The mean total score of quality of life and its domain mean scores for this study were lower compared to the study done in India where the total mean score of QoL was 95.42(±15.45) and the mean scores for the physical, psychological, social relationship and environmental health domains were 25.02 (±4.47), 22.90 (±7.34), 11.32 (±2.17) and 28.75 (±4.34), respectively [16]. The quality of life scores of this study was also lower than the study done in the UK which reported physical=54.57, psychological=45.93, social= 61.91, and Environmental= 61.00 [17]. In contrast, the findings of this study were higher than the study result reported by [18,19]. The potential explanation for this disparity may be due to, the differences in socioeconomic status, cultural context, health delivery system, and treatment strategy. The results of this study were consistent with the results reported from Addis Ababa with the mean scores of (mean ± SD) 41.3 ± 7.5, 42.8±8.2, 38.9±8.9, and 41.8±6.5 for physical, psychological, social, and environmental health domains respectively.

Living alone decreases the mean quality of life by 5.867 units compared to those who live with family. Additionally, living with relatives increases the quality of life by 1.469 units when compared to patients who live with families [20]. This finding was consistent with the study done by [20-21]. This could be explained by living alone compromises the quality of life of patients by decreasing social support that people live with families and relatives get an advantage by sharing the social, physical, and emotional resources, and living alone itself exposes them to mental illness and precipitates patients who have mental health problems [22,23].

Being poor adherent to medication decreased the mean total score of quality of life by 6.579 (p<0.05) points as compared to high adherence to their medications and those patients with moderate adherence decreases mean their quality of life by 1.662 (p<0.05) when compared to the high adherent. Those participants who were non-adherent to the medications were more likely to have a lower mean score of the total QoL scores indicating that they had a negative association with the total QoL scores. This study was supported by [24,25]. The episodic nature of the illness, the side effects of psychiatric medication, and the accessibility and cost of medications may explain this [26–29].

In this study having good social support increased mean their quality of life by 19.203 (p< 0.05) when compared to those who had poor social support and having moderate social support increased mean quality of life by 10.554 (p<0.05) when compared to who had poor social support. This finding is consistent with the study conducted by [30]. The potential explanation for this finding could be, that social support decreases the influence of mental illness on one's life, by improving self-esteem, alleviating the symptoms of emotional distress, and promoting life-long well-being in one's mental health, which could improve the quality of life.

The mean score for quality of life was lower than the mean score of many other studies. The living arrangement, medication adherence, and social support were associated with QoL. Efforts should be made to strengthen social support, ensure medication adherence, and patients are recommended to live with families and relatives to live a quality life for patients with SMI.

• There needs to have a plan to develop community support programs to increase and enhance social relationships and support for patients with severe mental illness and they need to be given the opportunities to build close social relationships & a healthy environment. This, in turn, increases their QoL.

• Attention should be paid to patients with severe mental illness on enhancing the adherence to their medications by using strategies like; patient education and treating side effects early because it will have a significant contribution to enhancing their QoL.

• Involving psychosocial support providers in the treatment of patients with severe mental illness is worthy to enhance patients’ quality of life by encouraging them to strengthen existing social relationships, initiating and maintaining social bonds, and professionals ought to encourage patients to live with families and relatives than living alone.

• The cause-effect relation between quality of life and associated factors was not established due to the study used a cross-sectional study design. So, future researchers are recommended to use an experimental study design to check whether there is a cause-effect relationship between variables.

This study investigated the quality of life and its associated factors of patients with severe mental illness on follow-up treatments. However, this study has certain limitations; WHOQOL-BREF focuses primarily on subjectivity, the domain of QoL, which can contribute to a lack of objective measurement and over-reporting of QoL in persons with severe mental illness.Since the design of the study was cross-sectional. The causality could not be verified. Thus, the association between quality of life and related factors cannot be viewed as cause and effect in this report. Answer bias may be added where the context characteristics of the respondent skews the response of the respondent.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was checked and approved by reviewers for its ethical soundness at the proposal phase at the Department of Psychology at the University of Gondar. A formal letter of permission was obtained from the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital. This study was approved by the University of Gondar ethics committee and it have been performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The confidentiality of respondents was maintained by letting the participant fill out the questionnaire anonymously. Completed questionnaires and computer data were and will be kept confidential by password security. Written informed consent was prepared and obtained from all participants after the purpose of the study was discussed with each client. The participants were given an awareness of the right to withdraw from the interview at any time they wish. Participants were assured that if they wished to refuse to participate, their care or dignity would not be compromised in any way. Participants also were informed that there was no expectation of additional treatment or any associated benefits and risks for them participating in the study. All the methods including the selection of research participants and data collection procedures were carried out per declarations of relevant ethical guidelines and declarations.

Consent of publication

Not applicable

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are not publicly available due to ethics regulations but may be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests

Funding

University of Gondar

Contributions

NB developed the proposal, analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the draft of the manuscript. MM revised the proposal, checked the data analysis, and revised the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the University of Gondar for funding the study and the University of Gondar Comprehensive specialized hospital for all forms of non-financial support provided for the study. Data collectors, supervisors, and study participants deserve special gratitude for their time and effort. Our gratitude also passes to Prem Kumar (Asst. Professor, College of Medicine & Health Sciences (CMHS, Wollo University) for his valuable feedback and revision of the manuscript for the English language.

Citation: Jember.B.N and Mengstie M. M. Quality of Life and Associated Factors Among Patients with Severe Mental illness at University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Ethiopia: A Cross-sectional Study. Prim Health Care, 2023, 13(8), 521

Received: 16-Aug-2023, Manuscript No. jphc-23-103039; Editor assigned: 22-Aug-2023, Pre QC No. jphc-23-103039 (PQ); Reviewed: 24-Aug-2023, QC No. jphc-23-103039 (Q); Revised: 26-Aug-2023, Manuscript No. jphc-23-103039 (R); Published: 30-Aug-2023, DOI: 10.35248/2332 2594.23.13(8).521

Copyright: ©2023 Jember.B.N. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.